MICHAEL REID BERLIN

NASIM NASR

ARTIST PROFILE

Nasim Nasr | Artist Profile

- Nasim Nasr

- 27 Oct—21 Dec 2025

- Berlin

Alongside Michael Reid Berlin’s career-spanning survey for Nasim Nasr – who will deliver an intimate talk and a personal tour of her exhibition on Saturday, 29 November – the gallery is pleased to present our recent conversation with the Tehran-born, Eora/Sydney-based artist, exploring the ideas, experiences and dualities that have propelled her multifaceted art practice for more than 15 years.

“The enduring thread is the dialogue between East and West – between my past in Iran and my present in Australia,” says Nasr of the connective themes that weave through the works now on view at Michael Reid Berlin. “Each project lives under this umbrella of seeking harmony between two cultural worlds. The narratives often begin with experiences from the East but are articulated and transformed through my life in the West. My work also speaks to the dualities we carry: black and white, pain and joy, the half-hidden and half-revealed. We live in constant tension between control and release, hope and hopelessness, usefulness and uselessness. These opposing forces shape us and form the visual and emotional language running through my practice.”

Now completing the prestigious Cité Internationale des Arts studio residency in Paris, awarded by Creative Australia, Nasr is among the most original and essential voices in Australian contemporary art. Spanning photography, sculpture, performance and installation, her work has been exhibited across Australia and abroad – most recently at Photo London – and is held in major collections, including the Art Gallery of New South Wales, Powerhouse Museum, Artbank and the Parliament House Art Collection.

Read our interview with Nasim Nasr below. Works from her solo exhibition can be explored and acquired online HERE, as well as at the gallery and by request.

For all enquiries, or to RSVP to Saturday’s public event, please email colinesoria@michaelreid.com.au

What were some of your early creative influences?

My earliest influences included contemporary artists such as Vanessa Beecroft and Shirin Neshat, whose approaches to performance, the female body and cultural identity deeply shaped my thinking. I was also inspired by European masters like Amedeo Modigliani and Alberto Giacometti, and by Persian poets including Forough Farrokhzad and Sadegh Hedayat. Their emotional depth, sense of vulnerability and explorations of identity have stayed with me throughout my practice.

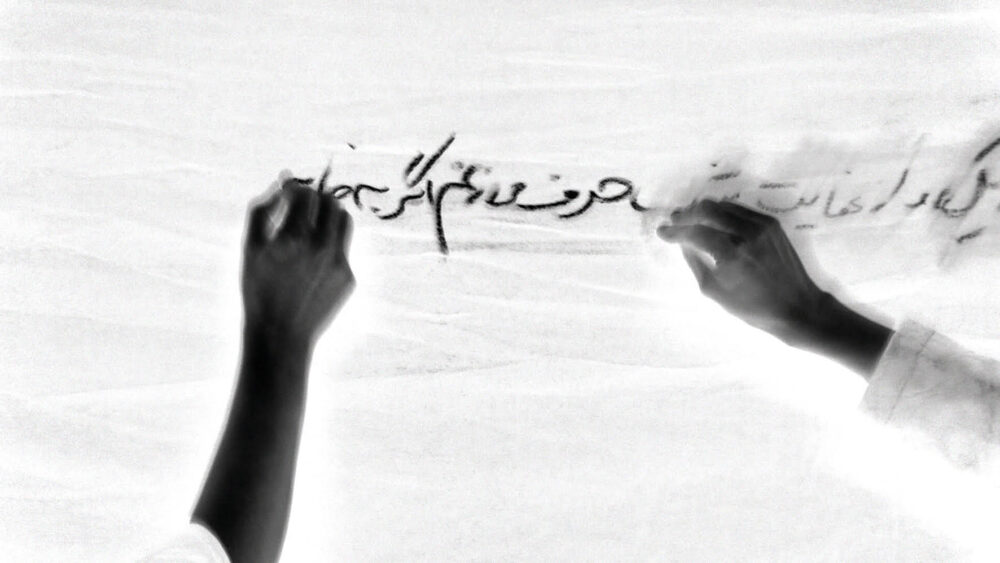

These influences continue to appear in works such as Erasure (2010), where I reference Farrokhzad by writing and erasing her poetry Rebirth. In Restless (2015), a paragraph from Hedayat about masks and hidden identities is read in multiple languages. My performance Women in Shadow (2011, 2018) also reflects the visual and conceptual inspirations I draw from both Beecroft and Neshat. Across my practice, their impact can be seen in my ongoing focus on double identity, visibility, and the tension between what is revealed and what is concealed.

What ideas, experiences or themes do you return to in your work?

Across my practice, I return to themes shaped by my lived experience as an Iranian-born Australian woman – my first twenty years in Iran and the rest in Australia. Since moving here in 2009, photography and video have become central to my work, and the contrast between growing up under suppression in Iran and now creating freely in Australia continues to inform my narrative. I frequently explore double identity, displacement, cultural bipolarity, and the tension between relief and restriction.

The emotional and cultural contrasts between my life in Iran and my life in Australia remain fundamental. My work often seeks to build a bridge between East and West, between my past and my present. And yet the more I try to escape or erase my past, the more it reappears in my work.

What have been some of your favourite career experiences?

One of the most significant breakthroughs came shortly after I moved to Australia in 2009. In Iran, I had been a painter and drawer focusing on nude female bodies—work I was never allowed to exhibit. When I arrived in Australia, I was taken to Maslin Beach, a nude beach in South Australia, with the idea that I could finally draw freely. Instead, that moment became a turning point. After years of censorship, I suddenly found myself in a place where nudity was permitted, yet I instinctively felt the need to cover myself. This contradiction pushed me toward photography and video, exploring self-censorship and concealment in a free country.

The first photograph I ever took – Image of Liberation (2010) – emerged from this experience and remains my most published work. That moment of cultural shock was also a creative pivot that reshaped my entire practice. Another breakthrough came during COVID, when I began working with glass – a medium I’d never imagined using. I revisited the historical tradition of tear collectors used by women in 17th-century Persia and reimagined them through a contemporary lens. What began as an experiment became a meaningful extension of my practice, and the work was received extremely well. Glass tear collectors have since become an ongoing part of my artistic journey.

Could you tell us about Forty Pages?

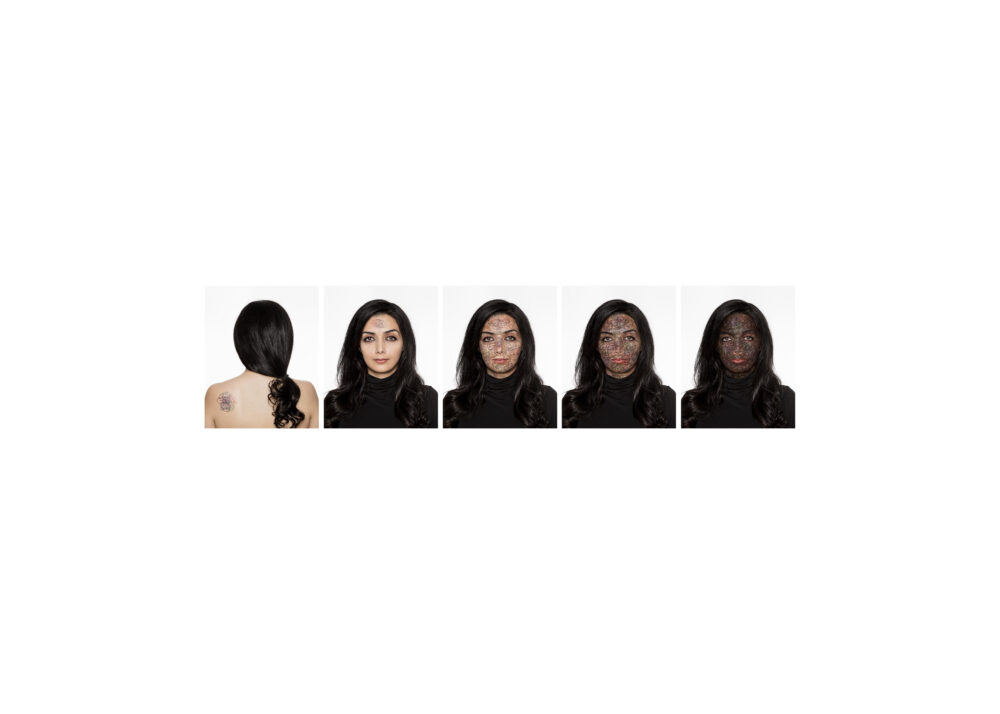

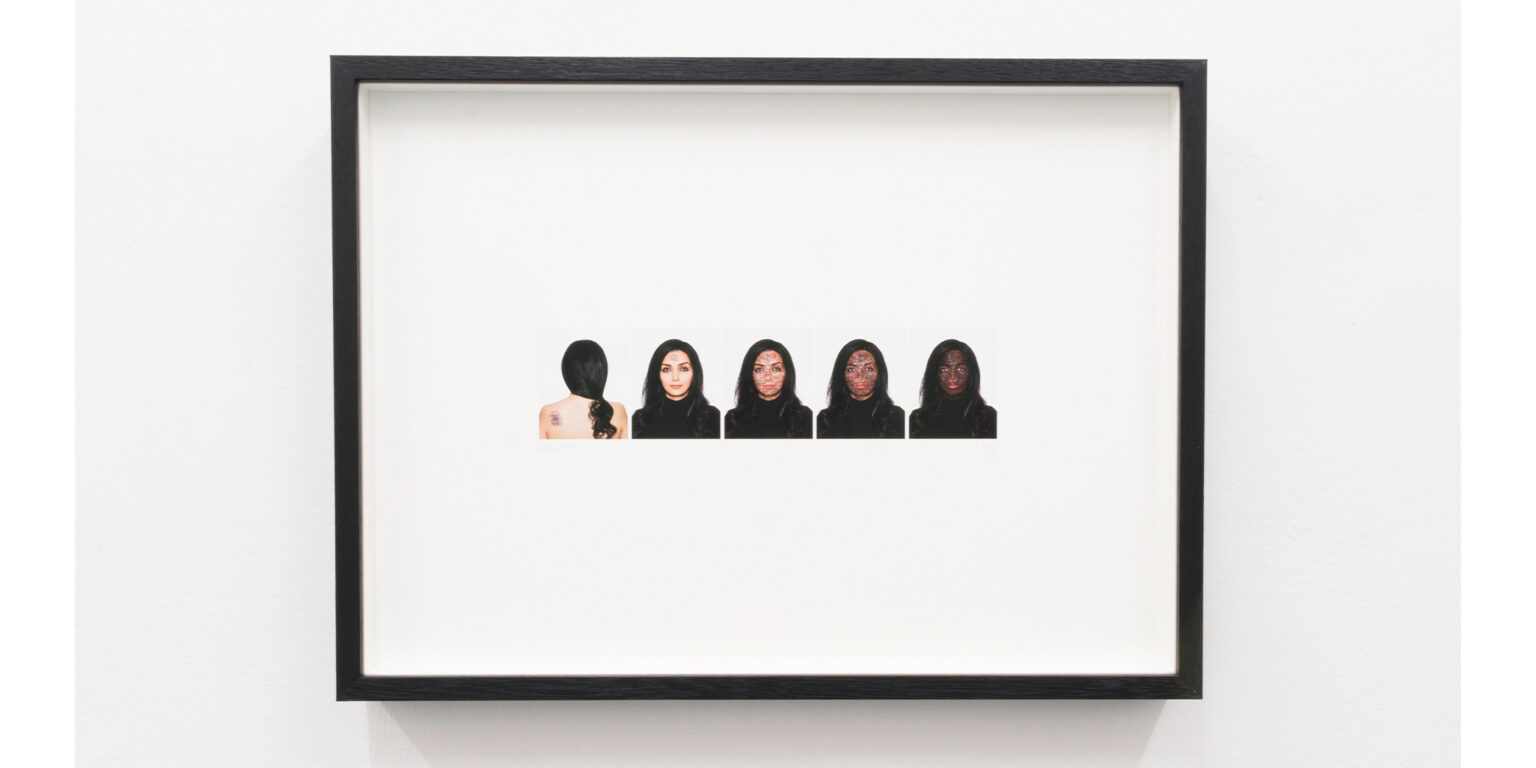

Forty Pages began from a place of pain, frustration and exhaustion. Between 2009 and 2015, I was exhibiting internationally while still travelling on an Iranian passport. The process was extremely difficult: visas, interrogations, long airport stops and the constant anxiety of being treated with suspicion. Every journey felt heavy. I wasn’t yet an Australian citizen and became acutely aware of how a single document could control your movement, your freedom, and even your sense of self.

When I finally became an Australian citizen in 2015, I felt compelled to close that chapter by transforming it into art. I used my old Iranian passport and its forty pages filled with stamps, marks and traces of those years of struggle. In the series, the accumulation of stamps becomes a form of scar tissue as I build them onto my face, layer by layer, until I no longer recognise myself.

The iconic portrait where I cover my face shows only Australian entry stamps – symbolising a new identity and a new sense of belonging. Half revealed, half obscured, it reflects the complexity of migration and living between cultures.

Ten years later, I see Forty Pages as an emotional and political self-portrait. It still resonates, especially as global borders and migration debates remain fraught. It reminds me how fragile—and powerful—identity documents can be. Today, I travel freely with my Australian passport, and physical stamps barely exist. The fact that the work continues to speak to others shows that these struggles are not just personal, but global.

How does photography relate to your broader art practice?

Photography is deeply connected to all facets of my practice. The concept always comes first, and then the medium that feels most truthful brings it to life. Photography often becomes the primary form because it captures the immediacy of my emotional and lived experience, particularly through self-portraiture. Using myself as the subject allows me to express personal narratives in the most direct, honest way. But my ideas rarely feel complete in a single form. Video, performance and installation expand the narrative and add layers of meaning. Many works begin as photographs but find deeper resonance through movement, sound or the physical presence of the body.

Although self-portraiture is central, I also cast other models when needed. My very first subjects were my brother and sister, whose presence allowed me to explore identity and family history from different perspectives. In this way, photography becomes both foundation and connective tissue – an entry point that opens into performance, video and installation.

Could you tell us about your latest body of work, Unspoken Words?

Unspoken Words is a photography and video series developed over the past two years in response to witnessing global conflicts and the pressure around speaking – or staying silent. Today, no matter how you speak up, there are consequences; yet remaining silent creates an internal battle. This tension between expression and suppression became the emotional starting point for the work.

I began by reflecting on my own “unspoken words”, the things I carry but often cannot voice. From there, the work expanded into a broader meditation on collective silence, political pressure and the emotional weight of global crises. The melting blue ink in my hands and mouth – formed from an ice cube – became the central metaphor. Blue ink was the first ink I used as a child to learn to write, and it is also the ink used today to sign treaties and documents that govern nations. In the series, the ink represents the fragility of truth, the instability of speech, and the way words can be frozen, controlled or dissolved. Through this visual language, Unspoken Words explores the struggle between voice and silence, the personal and the political, and the weight of what we say and what we don’t.

How do you view the series as a continuation and a departure within your practice?

Most of my recent works – Measure of Love, 33 Beads, Forty Pages, and now Unspoken Words – are studio-based photographic series. In many ways, Unspoken Words continues this direction, but it also marks a shift through its use of blue and its focus on more internal, global conflicts. My process often begins with what I call a “mental pregnancy”– a period of pressure, reflection and emotional build-up. Once the idea is fully formed, I move into the studio and create the work in a single, focused moment. I frequently place myself in the image when the concept emerges from lived experience, because embodying it allows the emotion to transfer directly to the audience.

In 33 Beads, for example, I confronted the tension between holding on and letting go—of memories, objects, traditions. Placing myself physically within the work made the tension feel authentic. Across all these series, the first take is often the strongest – the moment where emotion and concept meet honestly. With Unspoken Words, I continued this approach while pushing into new themes such as silence, consequence and global conflict. The melting ink introduced a new metaphor and visual effect, marking a subtle evolution in my practice while remaining connected to the psychological intensity of my earlier work.

Looking across the works in your Michael Reid Berlin career survey, what themes or shifts define the last decade of your practice?

The enduring thread is the dialogue between East and West – between my past in Iran and my present in Australia. Each project lives under this umbrella of seeking harmony between two cultural worlds. The narratives often begin with experiences from the East but are articulated and transformed through my life in the West.

My work also speaks to the dualities we carry: black and white, pain and joy, the half-hidden and half-revealed. We live in constant tension between control and release, hope and hopelessness, usefulness and uselessness. These opposing forces shape us and form the visual and emotional language running through my practice. Over ten years, you can see the shift from performance and self-portraiture into more experimental works with objects, materials and metaphor. I leave it to the audience to decide whether these works contradict, complement or complete each other. My aim is to open space for viewers to reflect on the tensions and harmonies between these worlds – just as I do in my own life.

What projects are you looking forward to in the coming year?

I am currently working on a fifteen-year video screening survey at the Cité des Arts Auditorium in collaboration with a French pop composer who is creating sound compositions in response to my visuals. Together, we are presenting fifteen years of my video art, accompanied by her live performance – a dialogue between image and sound that highlights the connection between East and West. At the same time, I am developing a new photographic series titled Imprints during my residency. I am also researching a rare 7th-century Persian book, exploring hidden histories of slavery, lust and loneliness experienced by women. This research will inform a new body of work I hope to release next year, alongside potential exhibition opportunities.