Andrew Sullivan: Painting Now 2024

- Andrew Sullivan

- 24 Oct—23 Nov 2024

- Eora / Sydney

Sulman Prize-winning artist Andrew Sullivan arrives in Painting Now with five extraordinary new works, representing the culmination of a brilliant career spanning more than 30 years and encompassing numerous accolades. In addition to his triumph at the 2014 Sulman, he has been a finalist in the Archibald Prize, the Blake Art Prize and the Mosman Art Prize and has exhibited widely across Australia and abroad.

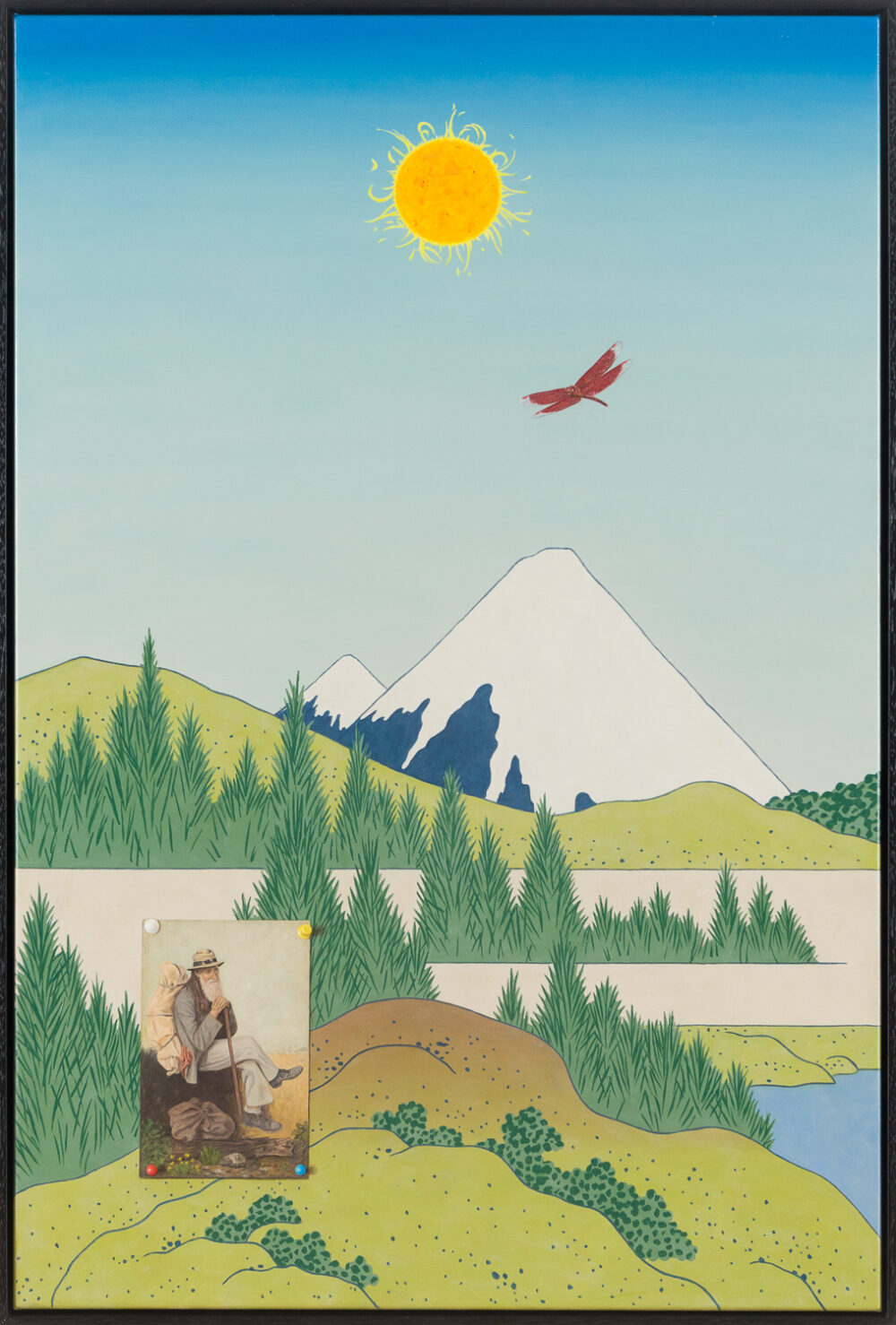

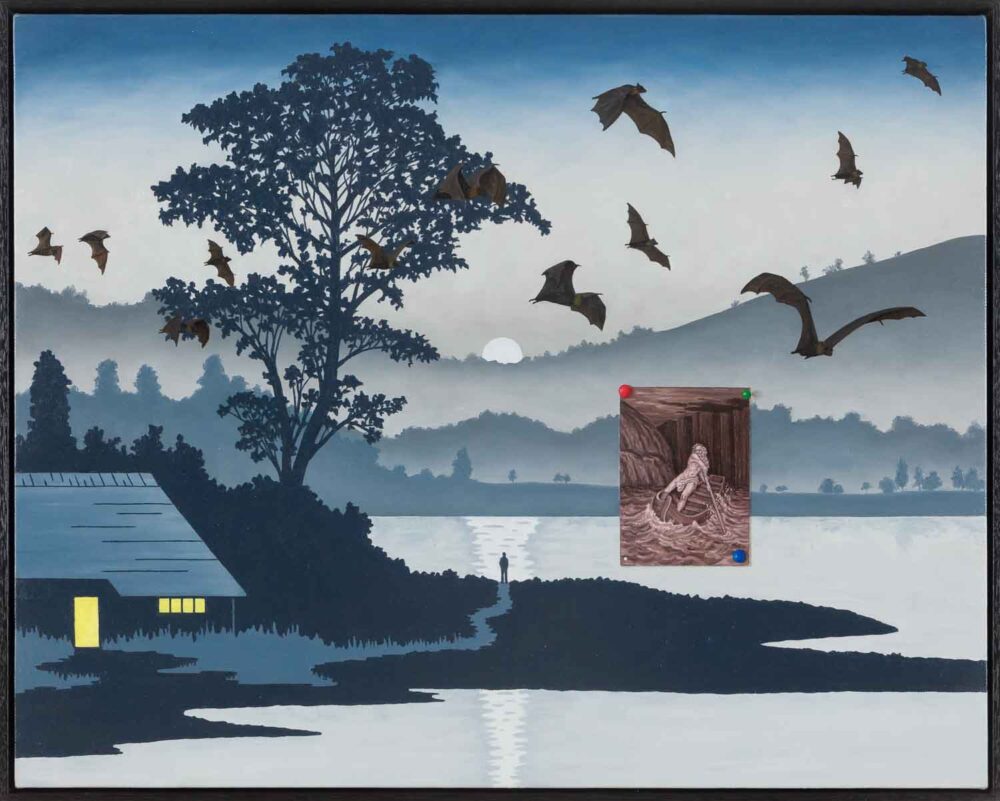

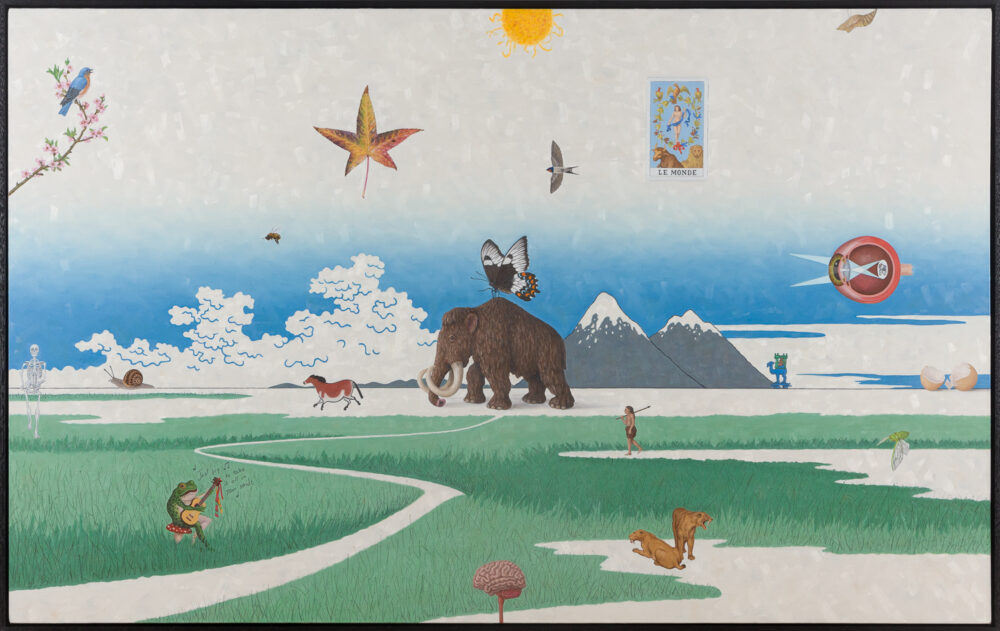

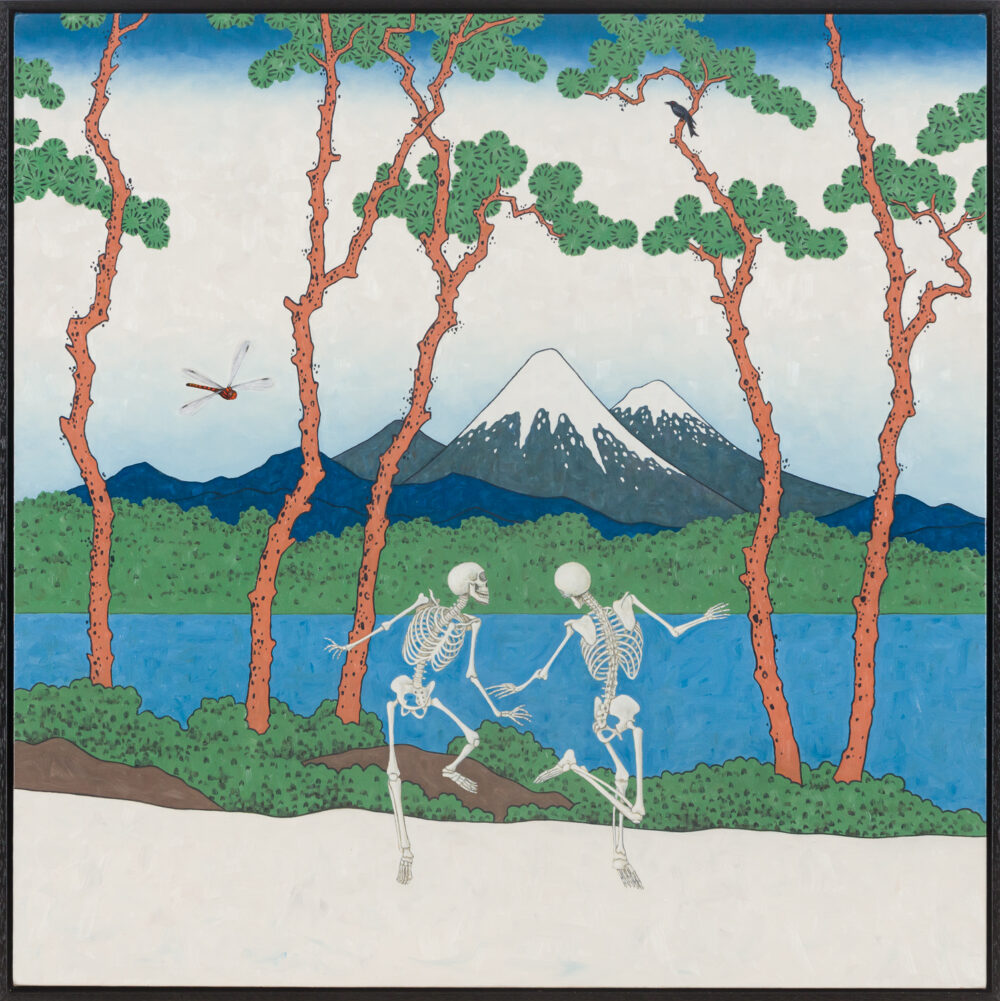

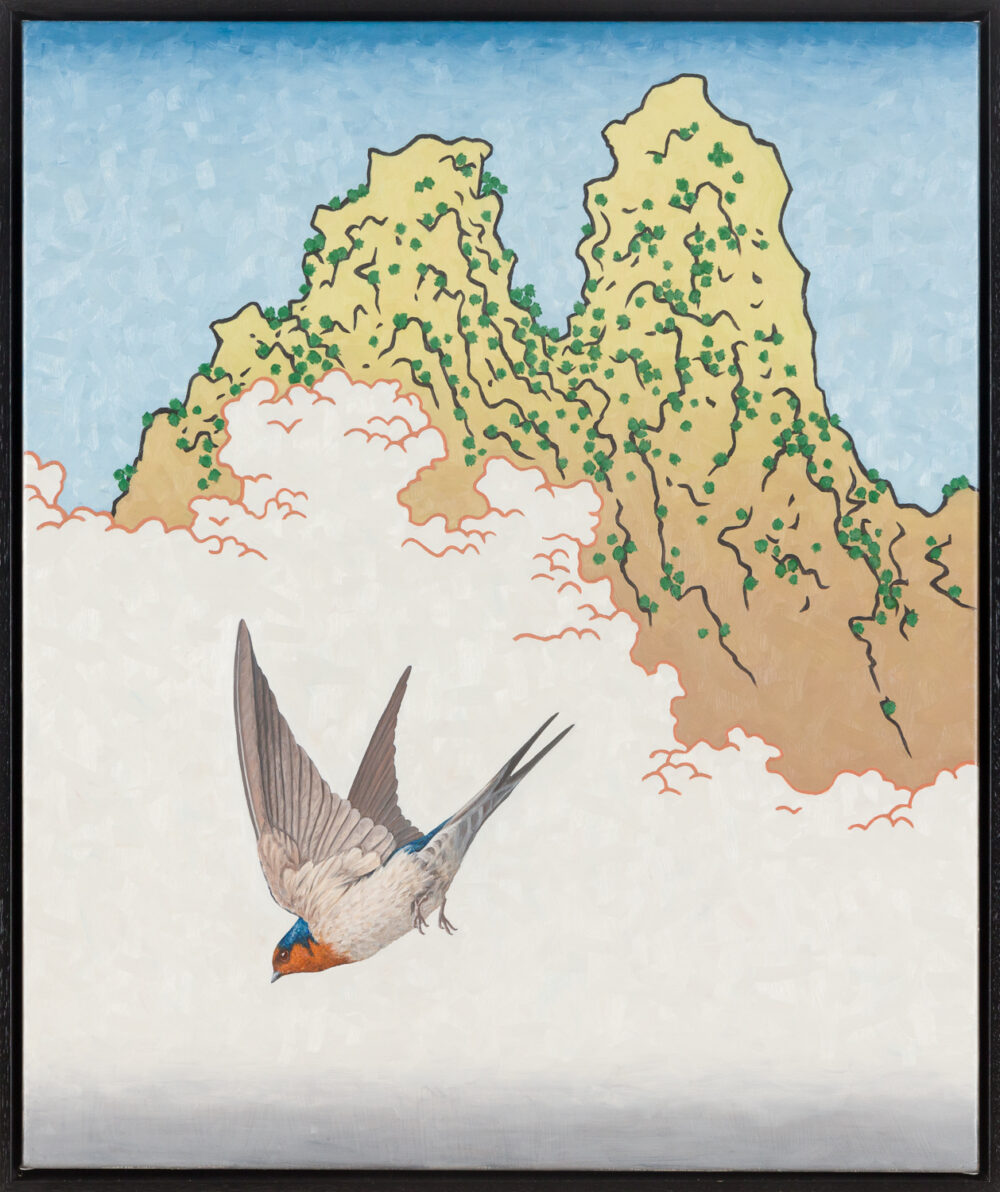

Sullivan renders his paintings with meticulous, masterful precision and a distinctive treatment of pictorial space – one that splices collagistic, trompe-l’oeil effects into tapestry-like landscapes reminiscent of Ukiyo-e prints. Against soft tonal gradations, his paintings present a wonderfully idiosyncratic array of motifs, allusions and allegorical figures, forming curious connections and enacting dioramic narratives tinged with humour, melancholy and vivid colour.

These symbolic details play out across Sullivan’s canvas like an exploded cabinet of curiosities. Traversing a vast spectrum of knowledge systems – from the scientific to the superstitious – as well as various aesthetic modes and moments in evolutionary history, they seem drawn together as if by the strange logic of dreams, memories, discursive trains of thought or the encyclopaedic parataxis of the digital sphere.

Sullivan’s paintings are held in the collections of the National Portrait Gallery, Artbank, Ballarat Regional Art Gallery, the National Art School and Buxton Contemporary. We are excited to present his latest body of work and invite collectors to register their interest below to receive priority access to his Painting Now series.

For more, please email dean@michaelreid.com.au

What were some of your early influences and how do they continue to inform your practice?

First and foremost, the Beatles were my earliest artistic influence. Painting-wise, the war paintings of Ivor Hele used to feature in the WWII magazines my brother collected. As a child, the energy and the atmosphere of these pictures excited me. I consider Hele to be Australia’s Goya. I also had a great love of cavalry charge paintings, the charge of the Scott’s Greys being one of my favourites. The amount of skill needed to execute these pictures still amazes me.

What initially drew you to painting?

I never wanted to be a painter, it was never on my radar. I did not understand that painting could be a language the way I understood music to be. I went to The National Art School to meet musicians and get a band together, which I did. The band broke up eventually; by then, I had finished art school and I did not know what else to do but give painting a try. Before I went to art school I had worked at a high-end framer as an ornamentor, gilder and frame restorer. We used to get many great old paintings in, and having a chance to physically handle them gave me a good insight into painting.

What have been some of your favourite career experiences?

Winning the Sulman was a good one. I was at my wits end at the time, having spent five years working on an extremely difficult body of work that no gallery was interested in. One always seems to be on the razor’s edge of not knowing whether one is inspired or deluded. Faith and belief are always of utmost importance for me. I was running out of energy, faith in myself, and money. I wondered if I was nothing but a fool to continue a practice that felt like it was destroying me. I did not give up, however, and one of the paintings from that body of work won the prize.

Could you tell us about the works featured in Painting Now?

Dad used to trade with the Japanese POWs during the war. We always had Japanese things around the house. He made several visits there after the war. The Japanese aesthetic appealed to me greatly; the simplistic perfection of design and the reference to nature had an enormous influence on me.

Is there a narrative running through your Painting Now series and how does this reflect the direction of your practice?

There is often a narrative to my paintings, usually one of thought and reflection. These five paintings were a bit of a sideline that I wanted to experiment with. The Japanese woodblock prints make a very effective imaginary landscape setting. Rendering them in oil was a challenge and each one is a bit different in its approach. I am still using elements of the woodblock aesthetic in my current work. I constantly return to it as I do most of my symbols and motives. The language and the art of painting is an ancient and profound one. I have been working on it for many years. It began with our ancestors painting on cave walls. It is never taught in art schools; very few seem to recognise its existence the way that I see it. Again, it is a fine line between inspiration and delusion or intuition and imagination. I will let the paintings testify as to my true state of being. My words are nothing but words, while paintings are actions.