PAINTING NOW | Columbiere Tipungwuti

- Columbiere Tipungwuti

- 4—28 Dec 2025

- Download now

- Eora / Sydney

Columbiere Tipungwuti paints the celestial figures of Tiwi ceremonial culture – Japarra, the moon-man who brought mortality to the world, and japalinga, the stars whose ochred forms adorn dancers’ bodies in ceremony and yoyi. “I paint Japarra because I want to tell that story from long ago – what he did on earth and keep that story going,” says the artist. The story tells of Japarra’s fateful encounter with Purukuparli and Wai-ai, which led to the death of their child and Japarra’s ascent to the sky, where his white light reminds the Tiwi people of the cycles of life and death.

“In parlingarri – old time – Japarra saw the family out bush; the baby died from the sun, and Japarra wanted to take him up for three days and bring him back alive. But the father said, ‘Karlu’ – ‘no’. After fighting, Japarra flew up and stayed in the sky to become the moon and look down on the whole world. Now everyone around the world can’t come back; they must follow that father and his son and die when it is their time.”

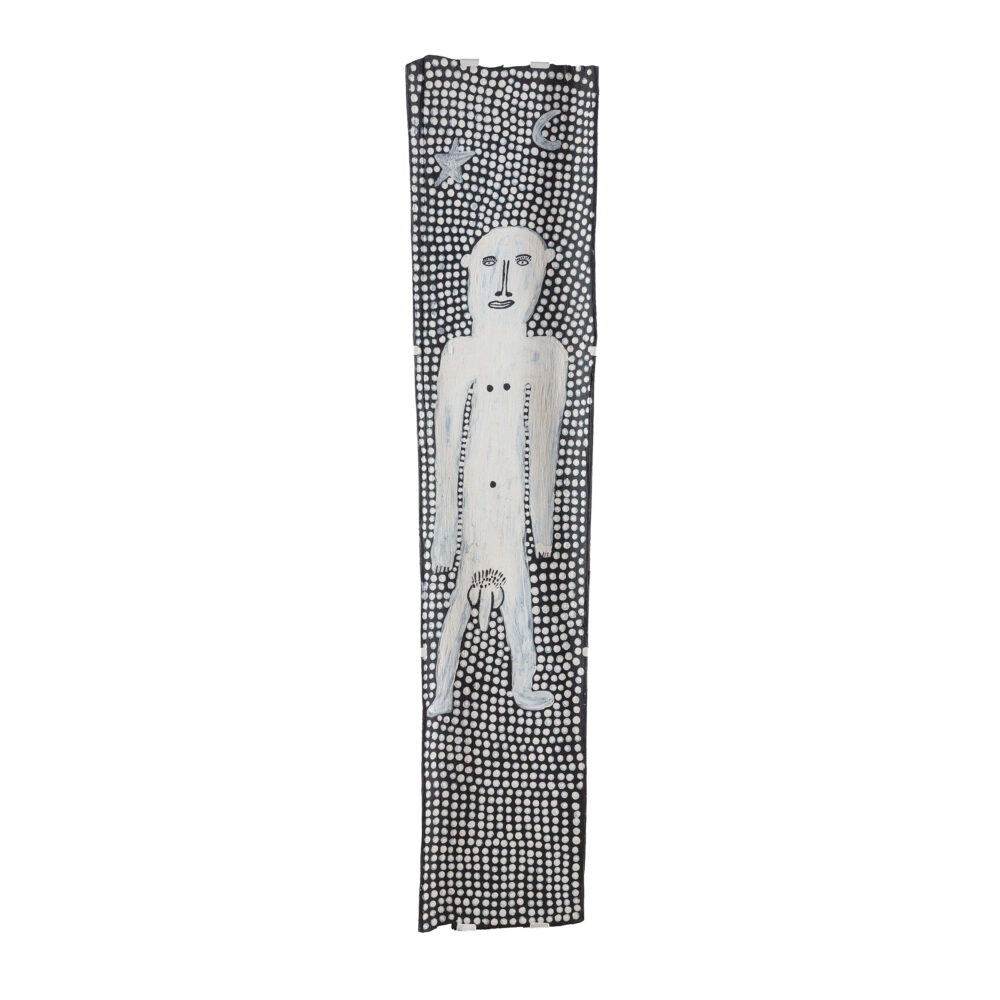

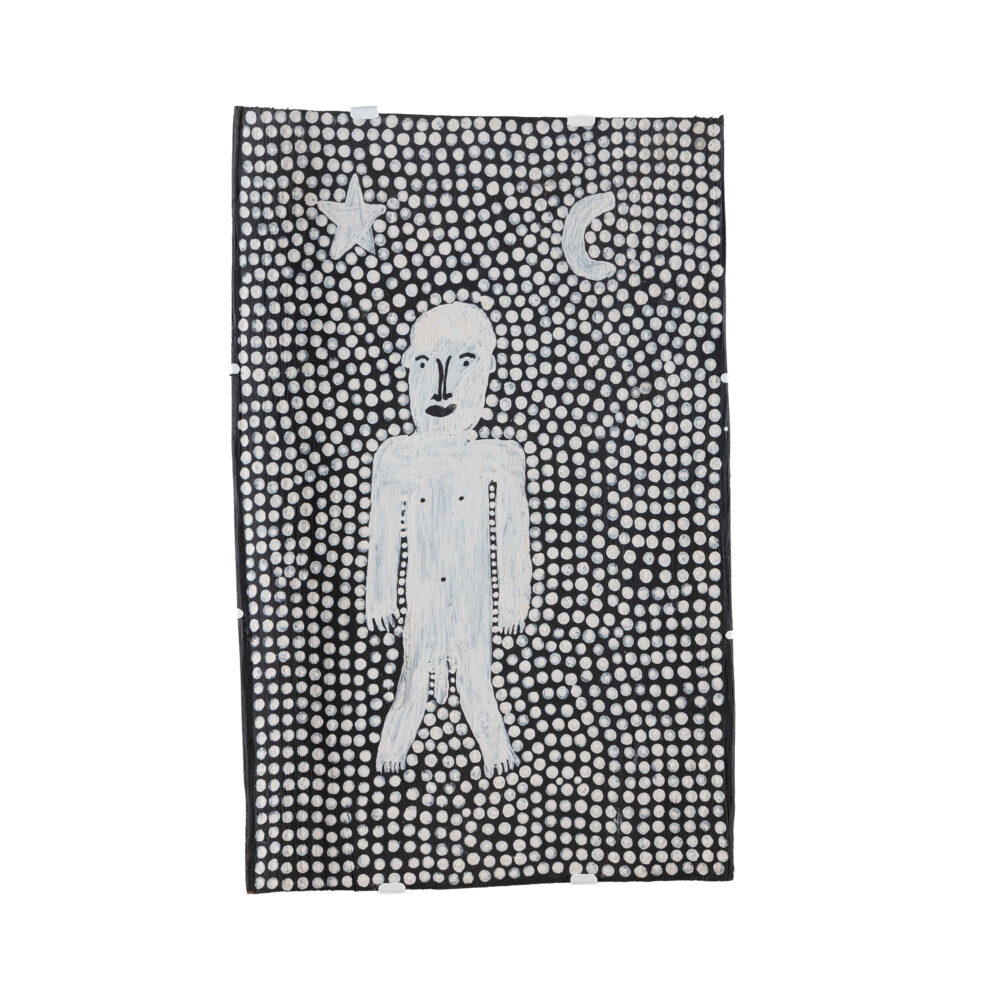

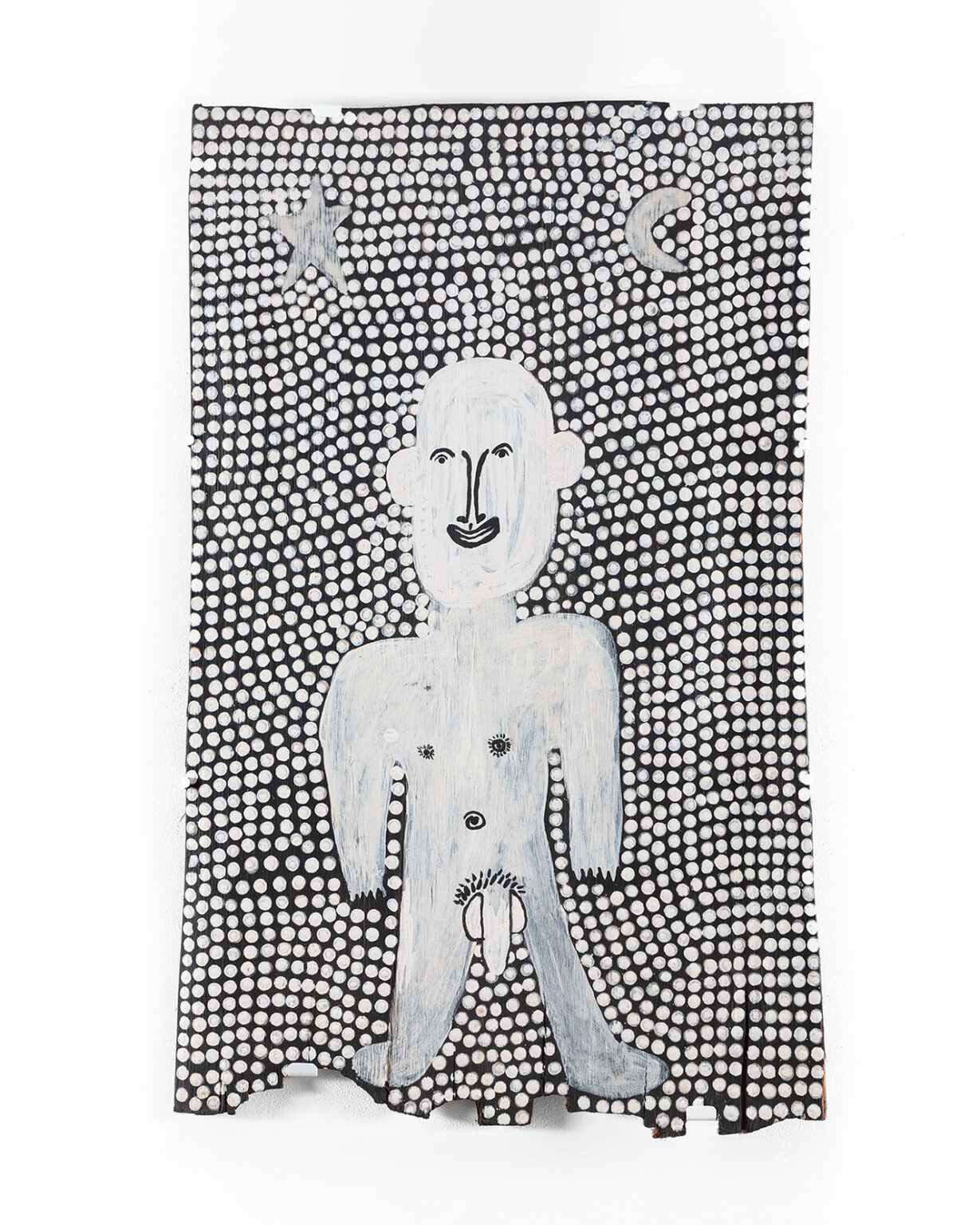

On bark and canvas, Tipungwuti renders the ancestral moon-man in stark black and white, his face striking, solemn and compelling. “Japarra is white – the moon-man has a white body. All the stars are white and the moon is white too,” he explains of his elemental palette, made from white ochre gathered on Country at Wurankuwu.

“I want to share my story and the story of my painting with people from all over the world,” says Tipungwuti, who also has a background in dance – performing ballet in Sydney in the 1980s and yoyi on the Tiwi Islands.

A finalist in the 2024 National Emerging Art Prize, Tipungwuti showed his paintings to great acclaim this year at UNSW Galleries in Parlingarri Amintiya Ningani Awungarra: Old and New, a widely celebrated exhibition curated by José Da Silva with Jilamara Arts. In Painting Now, Tipungwuti continues this lineage, transforming Tiwi creation stories into powerful, luminous images that bridge earth, sky and spirit.

“In years gone by, there was a strong Tiwi tradition of producing nude figurative ironwood carvings that tell [Japarra’s] story,” writes cultural critic and researcher Tristen Harwood. “Tipungwuti’s paintings draw on these important cultural influences to create innovative works grounded in his knowledge of the old stories and connection to longstanding practices of storytelling.”

For enquiries, please email dean@michaelreid.com.au

Explore more from Painting Now HERE.

What were some of your earlier artistic influences?

My close family did not paint, but when I grew up I was thinking about that story Purukuparli, Wai-ai and Jinani (Tiwi Creation Story) when they were out bush. When Jilamara opened in 1989 I started painting here. I have lived at Pirlangimpi and painted at Munupi Arts in between, but still going here at Jilamara.

What initially drew you to painting and how has your approach developed over time?

When both Tiwi people and murrintawi (non-Tiwi people) ask me why you doing this Japarra (moonman) painting I tell them that this is my story. Japarra offered to bring that baby back to life after three days, but because the father (Purukuparli) of the son (Jinani) said “no”, we all have to follow that baby and die when it is our time.

What have been some of your favourite career experiences?

When I decide to stop in Milikapiti and work at Jilamara full-time and not move around so much between the communities on the islands – Garden Point (Pirlangimpi) and Nguiu (Wurrumiyanga). Then I started making Japarra paintings and it has gone on from there. Last month I did my first Jilamara trip to Sydney and danced at the opening at UNSW.

Could you tell us about the body of work you have created for Painting Now?

I’ve been working on my painting for a long time, but the Japarra (moonman) painting I make now is from the last couple of years. I now only use white ochre because Japarra – the moonman – is white and the stars are white too.

Is there a narrative or throughline in your Painting Now series?

The story of the painting is from parlingarri (old time) when there were no cars or houses on the land. The story is of Japarra when he saw the family Purukuparli, Wai-ai and Jinani when he was out bush. Then he went away with that woman and her son Jinani died from the sun. He then fought with the father one. Japarra, he wanted to bring the baby back to life, take him up for three days and bring him back alive, but the father said “Karlu” – “no”. After a while they were fighting and Japarra flew up and stayed up in the sky to become the moon and look down on the whole world. So now everyone all around the world can’t come back, they have to follow that father and his son and die when it is their time.

How do you hope viewers will engage with your work in Painting Now?

I want murrintawi (non-Tiwi people) to look at that painting and learn about the story about long time ago on the Tiwi Islands. I want to share that story with the world.

I want to share my story and the story of my painting with people from all over the world. I haven’t always been a painter. I’ve also been a dancer. Ballet dancer in Sydney in the 1980s and also a dancer here on the Tiwis – my totem is Jarranga (buffalo) and I dance this at ceremonies. Now I am a painter and can share my story through my Japarra (moonman) paintings.