Darren Wardle: Painting Now 2024

- Darren Wardle

- 24 Oct—23 Nov 2024

- Eora / Sydney

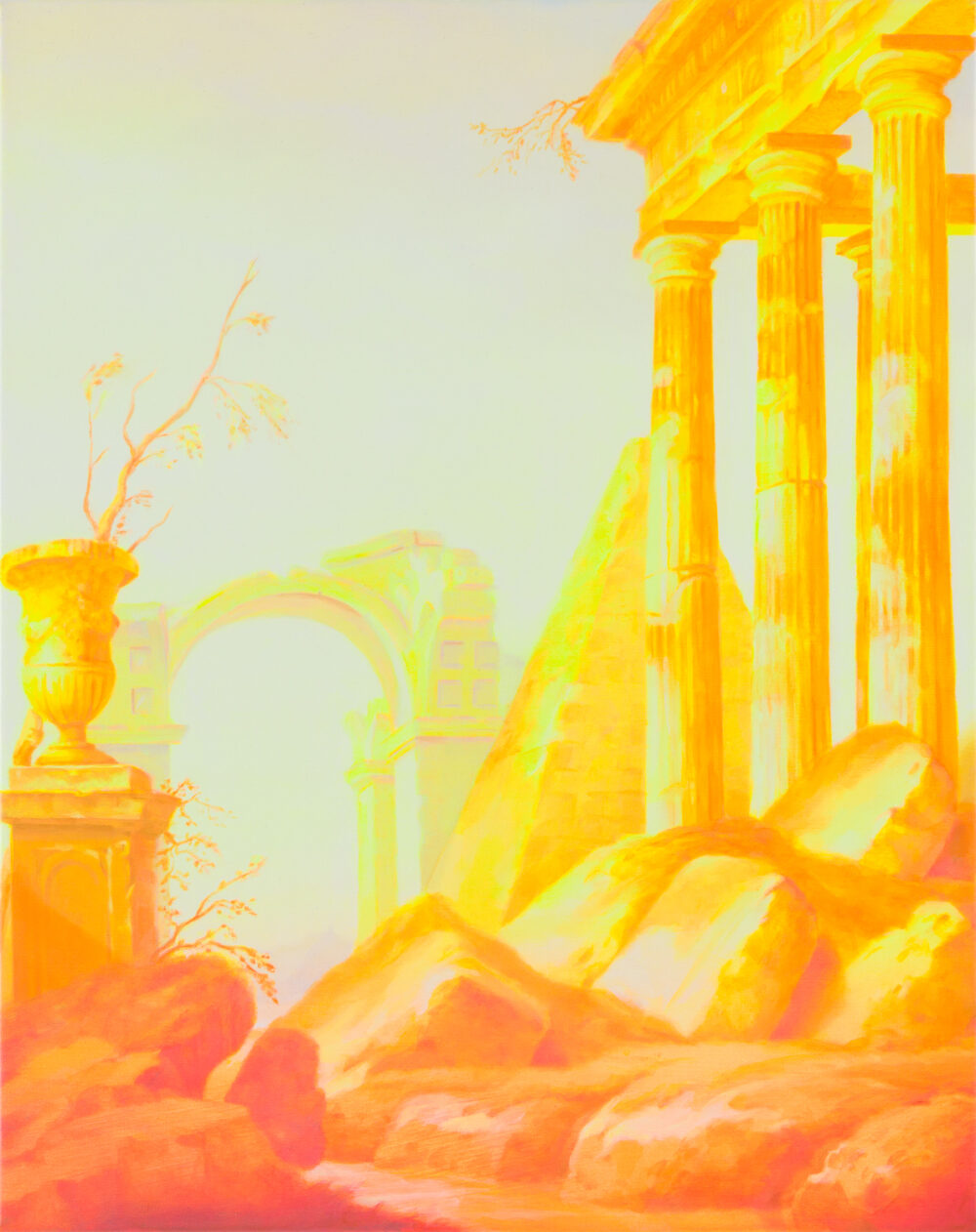

Naarm/Melbourne-based artist Darren Wardle constructs epic architectural dreamscapes in spectacular decay, suspending the past’s crumbling monuments in impossible, neon-soaked futures where the material and virtual entwine.

Anchored by his monumental work The Afterlife of Things, Wardle’s Painting Now series is a fabulous visual odyssey through collapsed utopias and overgrown ruins, all suffused with a perfectly controlled, gauze-like effervescence in delicate tonal gradations. Drawing on his doctoral research and recent experiments with AI-assisted technologies, it melds the ascendant possibilities of the digital sphere with a masterful approach to painting honed over a four-decade career.

“We are enveloped in ruination. Empires decline, structures decay and landscapes fall into ruin, along with our bodies,” says Wardle, who was recently an artist in residence at the globally renowned Leipzig International Art Program. “Decay and ruination are undaunted by technological obstacles; they make no distinction between us and nature.” A lecturer and PhD candidate at the Victorian College of the Arts, Wardle has shown widely at galleries and museums across Australia and abroad – including London’s Saatchi Gallery – and was commissioned to complete a large-scale wall mural for Shepparton Art Museum.

The artist’s formal enmeshment of painting tradition with cutting-edge technology is synced to his work’s conceptual crux; its optically charged entanglement of the past and future, real and imagined, beauty and decay. By breaking painting open these experimental possibilities, Wardle embodies the ambitions of our Painting Now program. Work from the artist’s extraordinary new series can now be previewed and acquired by request at Michael Reid Sydney.

For more, please email dean@michaelreid.com.au

What were some of your early creative influences?

There are many. At art school, I was influenced by Sigmar Polke, Max Beckmann, Philip Guston, Giorgio de Chirico, Jasper Johns, Jean-Michel Basquiat, Jon Cattapan, Anselm Kiefer, Martin Kippenberger and a lot of Neo-Expressionists from the Moritzplatz group in Berlin.

At the end of a trip through Europe and the USA when I was 21, I chanced upon an Ed Ruscha retrospective at MOCA LA that had a profound impact on me. His cool pop imagery and conceptual use of materials in relation to his suburban subject matter changed the way I thought about my work and how I wanted to position it. Ed cooled down my whole approach. It became more personal and pre-planned and gave me licence to focus on the suburban environment that I grew up in. This led to an enduring obsession with architecture, the built environment, and its relationship to nature.

Soon after, I began to look more closely at John Brack, Robert Rooney and Howard Arkley. They challenged the myths underpinning Australian landscape painting and positioned the suburbs as an authentic reflection of how most Australians live, which provided me with a local context for what I was doing.

Some of these artists still inform what I do to various degrees, but now my taste is much broader, and I look beyond painting for inspiration.

What initially drew you to painting and how have you developed your practice?

I didn’t get into painting until my teens. After a lacklustre VCE art experience, I spent a year studying painting at Box Hill TAFE under Stephen Wickham. He encouraged me to ditch acrylic and use oil paint. I loved the intensity of colour, its juicy slipperiness, longer drying times to manipulate the paint, all the different mediums, the smell and grand history of it; I was immediately hooked!

I have returned to themes, particularly those related to architecture and the built environment, and the impact of technology. Inevitably I have tendencies and habits I try (and fail) to break, but style is not a driving motivation and I don’t want to be pinned down by it. I tend to use colour with a high-key crispness, and I’m drawn to combinations that look synthetic or unnatural. There are recurring compositional dynamics; scenes that indicate habitation but feel dystopian and tend to have a digital accent. My approaches and techniques have varied with the feel of the subject matter.

My work has gotten close to abstraction at times and moves between hard-edged flattened approaches and more fluid or blurred ones to articulate space. Techniques and methods encompass conventional acrylic and oil painting, a lot of collage and digital work, photography, printmaking and, lately, experiments with AI and video.

What have been some of your favourite career experiences?

International exhibitions and studio residencies stand out. I was fortunate to be able to live and work in New York and Los Angeles during the height of a new boom in painting in the 2000s. Things seemed to line up. I met and showed with interesting artists, some that I’d been interested in for a while, so to be able to develop my work and exhibition profile among all that energy was significant. It was an art school dream that came true.

More recently, I was in residence at the Leipzig International Art Program in Germany, which was similarly energising at a time when I was shifting the direction of my work and I was in a few shows there. Leipzig has a tight community of artists, an interesting music scene and is close to other cultural centres such as Berlin, Chemnitz and Dresden. It also has a unique cultural history and is littered with ruins from the GDR era. I still think about it.

This year I spent a hot month in Eastern Europe visiting Socialist Modern architectural ruins and ‘spomeniks’ in Romania, Serbia and Croatia. Apart from blowing my mind, this field trip was extremely productive. I was able to develop a substantial photographic and video archive that will serve as reference material for future paintings, prints and video work for quite some time. I’m really excited about this!

Winning the Gold Coast Art Prize with a small but confrontational Head Case Study portrait was stunning. I thought I had a slim chance of getting in and snowflake’s chance in hell of winning, it was hard to believe!

Could you tell us about the artworks featured in Painting Now?

Exponential Horizon is an AI-enhanced digital video, made in collaboration with my artist friend Brie Trenerry. It was projected inside an old disused bank in Prahran as part of an exhibition called DAS KAPITAL in late 2023. High-resolution documentation of about ten recent paintings of mine was fed into a generative AI program for moving images, which produced numerous short clips. The clips were directed by written prompts extracted from my PhD and Brie’s wild prompt interventions. The idea was to confuse the program to encourage ‘data hallucinations’, an idea I found extremely appealing.

Screen grabs from Exponential Horizon and clips that didn’t make the final edit were cut and collaged in Photoshop to create new compositions. The Afterlife of Things and Persistent Illusions are paintings that evolved from this process of mediation between analogue and digital modes. Both are based on distortions of paintings featuring discarded mattresses in states of decay that were collaged into images I took of an abandoned school near where I grew up in Melbourne. Now they’ve ended up being AI-assisted mash-up paintings that speculate about future ruins.

Capriccio Study 1 and Capriccio Study 2 are based on digital collages of fragments taken from ruin paintings by famous 18th-century exponents of the genre. I decided to paint them in fluorescent acrylic to dislodge them from their historical origin, reposition them as building sites, and symbolically reference hi-vis safety clothing warning of potential dangers.

Soft Core was based on a manipulated photo I took of a defiant-looking discarded mattress in New York after a blizzard. I liked the soft winter light falling on it added the rainbow label to make it look optimistic.

Is there a narrative running through your Painting Now series and how does this reflect the direction of your practice?

This group of works are ruin fantasies that have come out of my PhD research and jump around between past, present and future. Temporal mutability – the feeling of hovering in time – is present in the experience of ruins and part of their attraction. Ruins, decay and obsolescence are distinct aspects of my practice right now. As the PhD progresses, I’ll be experimenting with even more exaggerated temporal disjoint and formal distortion made possible with the assistance of new technology.