MICHAEL REID BEYOND

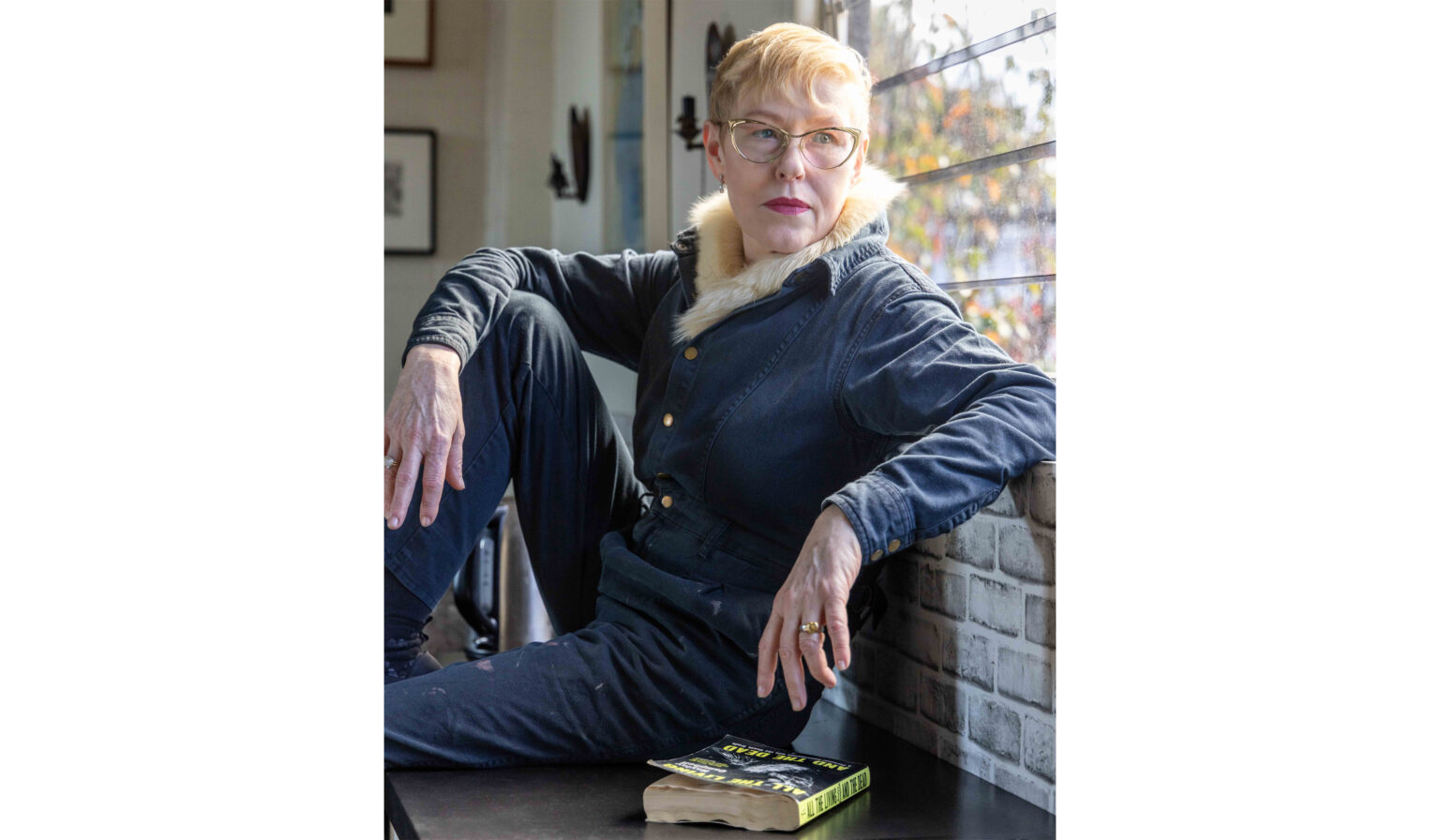

Linde Ivimey

ARTIST PROFILE

To celebrate the news of Michael Reid Sydney + Berlin’s representation of Linde Ivimey, writer Carrie McCarthy met the artist at her Eora/Sydney home and studio to discuss the ideas, experiences, and material approach that guide her globally celebrated sculptural practice.

Perched on a stool at a workbench surrounded by an archive of totems and keepsakes, Linde Ivimey sits with her head bowed in concentration. Nearby, an audiobook plays; the text, a book on the mythology of ancient Mesopotamia. Her fingers move rhythmically as she pulls twine through a collection of tiny star-shaped bones, weaving them into a delicate lattice that will soon drape across a toddler-sized form waiting nearby.

“I’ve been making something out of nothing my whole life.”

Linde Ivimey

When the last piece is threaded, it will be pinned into place, before adding pearls or quandong seeds or a gemstone she once used to wear. She might add a flourish of peacock feathers or a veil of hand-dyed silk. Eventually, the form’s character will emerge – an uncanny evocation of Ivimey’s contemplations as she shaped it into being.

Bones have been an intrinsic part of Ivimey’s idiosyncratic art practice for more than 20 years, representing strength and fragility, mortality and survival. Inspired by a childhood fascination with the wishbone from a Sunday roast, Ivimey began using bone as the basis of her experimentations when she was still too young to understand she was tapping into a history of artmaking that stretches back to Paleolithic times.

As she and her art practice matured, Ivimey gravitated towards the symbolism of Ancient Egyptians, Etruscans and the Cycladic people, as well as artists such as Francis Bacon, Lucian Freud and Balthus, whose depictions of fleshy bodies and desire still inform her work.

While travelling through Europe, Ivimey discovered an appreciation for the stories of saints and their patronages, and studied Edward Hopper, whose ability to make the ordinary compelling resonated deeply.

Her sculptures evolved to incorporate more talismans and remnants of domesticity. A ribbon from a special gift, champagne foil from a shared celebration, laundry lint, remnants of candles, bits of broken jewellery; everything had potential and all of it had meaning.

“It’s wonderful to have the works here in my studio. They’re very much like family members. Babies I haven’t had are really growing up … renegade little teenagers now.”

Linde Ivimey

It’s impossible to feel alone in Ivimey’s studio – there is always a presence there, demanding to be recognised. If it sounds a little magical and esoteric, to a certain extent it is.

Many collectors, curators and gallery staff have mentioned feeling protective of Ivimey’s sculptures in a way that extends beyond the standard need to care for a valuable piece of art.

Despite being devoid of any recognisable facial features, they personify recognisable emotions, hopes and vulnerabilities. There are definite dark undertones, but there is also a strong impression of humour and playfulness.

Though not always strictly autobiographical, the visual language Ivimey employs is deeply personal. Her work is both a salve and an invitation to better understand ourselves – a way to make sense of life and reflect on humanity.

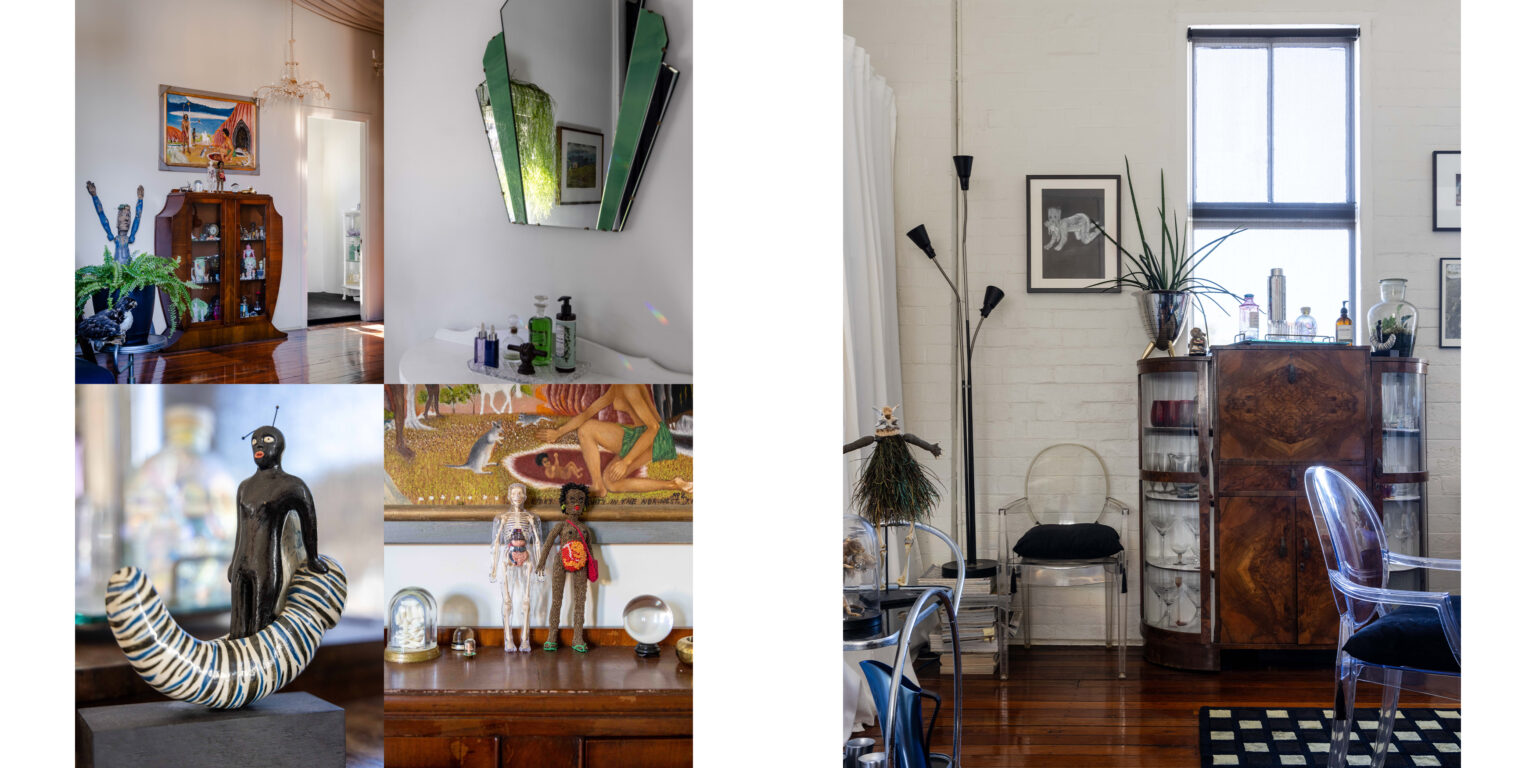

Perhaps the humanness inherent in her sculptures exists because there is no clear delineation between Ivimey’s art practice and her life. Her home, above her studio, is less a dwelling than an art installation within which she finds sanctuary and serenity.

“What I live out in my art is what I let out.”

Linde Ivimey

Located in an area of inner Sydney once known as a centre of manufacturing, the converted warehouse holds the imprints and energy of the many makers who came before – carpenters, distillers, printers, and photographers have all made this place their own. Warm timber floors reflect the building’s history, as does the staircase, the steps of which dip in the middle from almost two centuries of footfall.

Swathes of fabric hang from exposed beams to break the cavernous space into discrete areas for researching, making, dining or entertaining, though no one thing in her life is ever really separate from another.

During the day, sun beams through long sash windows, illuminating piles of heavily-thumbed books and curious collections such as antique pocket watches, rosary beads, and a cabinet of uranium glassware.

“There is one hand directed towards death, but there is another hand directed towards rebirth – another use, and another life.”

Linde Ivimey

At night, the living space is lit softly by chandeliers of strung bone. Though orderly, every surface shows signs of an artist for whom making is a compulsion even in her downtime.

Pencil sketches on brown notepaper sit alongside notepads with lists of possible exhibition titles. Dainty Swarovski crystals sparkle across a small black square of velvet, some already strung onto fine cotton strands. To the side, burgeoning experiments with clothing ties are beginning to come together. Though there might be simultaneous projects on the go, it feels cohesive rather than erratic.

Ivimey is pragmatic enough to understand why audiences might be confronted by the inclusion of bone in her work, though, as she says, “bones are the stuff of us.” Prior to discovering chicken wishbones, Ivimey’s childhood dream had been to become a doctor, and she remains intensely curious about the biology of ‘being’.

She never stops learning, investigating, and evolving, and neither do her sculptures. There have been times of significant ill health and upheaval throughout her career, but the one constant has been her ability to pour those experiences into her art in such a way that they reflect the complexity of all our lives.

“I think we spend a lot of our adult life reconciling our childhood and I think that happens for me through my sculptures – making… tending to those figures… They’re meant to do something… They’re meant to be therapeutic. A lot of the sculptures have content that helps me look after the little girl in me I still need to look after. And the big grown-up woman.”

Linde Ivimey