MICHAEL REID BEYOND

Murray Fredericks

ARTIST PROFILE

On the eve of the announcement that acclaimed Australian contemporary photographer Murray Fredericks will be represented by Michael Reid Sydney + Berlin, the gallery team met the artist at his Eora/Sydney home and workspace to discuss the creative influences, conceptual inquiries, and intrepid engagements with elemental extremes that have underpinned his singular practice.

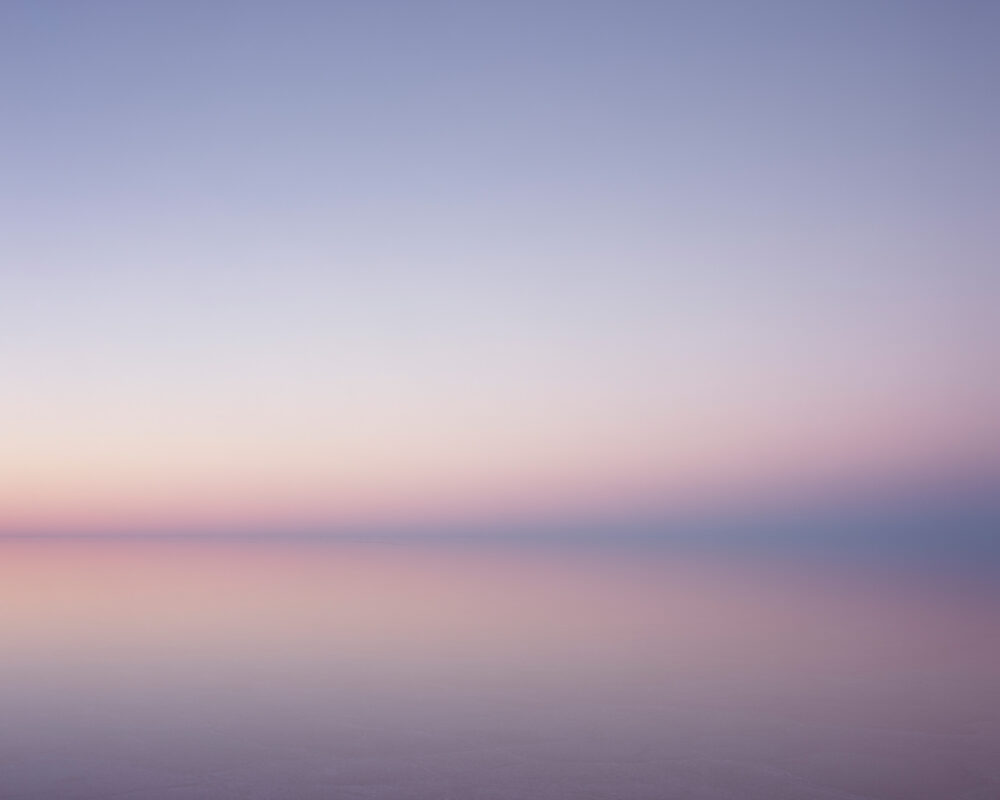

“Rather than treating landscape as scenery, I understood it as a field in which perception unfolds, where light, space and duration become the true subject,” says Fredericks in our interview, in which he reflects on several pivotal projects within his celebrated career, from his seminal, decades-spanning Salt series to more recent bodies of work such as Blaze (2023). “The landscape functions as the medium through which emotional and psychological states are registered, particularly those that emerge through prolonged solitude and complete immersion over weeks or months at a time.”

Read our conversation with Murray Fredericks below alongside a selection of photographs from the foundational bodies of work he discusses in our interview – Salt, Hector, Vanity, Icesheet (Greenland), Array and Blaze. Works from these series are newly available to acquire from Michael Reid Sydney. For enquiries, please contact dean@michaelreid.com.au

“The landscape functions as the medium through which emotional and psychological states are registered, particularly those that emerge through prolonged solitude and complete immersion over weeks or months at a time.”

MURRAY FREDERICKS

___

Could you tell us about some of the earlier creative influences and the experiences that propelled you towards your photographic practice?

From as young as I can remember, I noticed that I became a different person when I was in the natural landscape. In open environments I experienced a kind of psychological freedom that I couldn’t access elsewhere. I sought those spaces out constantly, and that impulse has remained central to my life and work.

My earliest engagement with landscape photography was personal and almost naïve. I learned the methods of Ansel Adams and began working with black-and-white film, eventually moving into large-format cameras during extended periods of solitary trekking – six months crossing the Himalayas from east to west, long stretches in Patagonia, and five summers and a winter living and walking in South West Tasmania. I lived with the camera in isolation for as long as I could. Those years were formative not only technically, but experientially. They established a relationship between solitude, duration and perception that continues to underpin my practice.

While in South America, I encountered a salt lake for the first time. One evening I walked alone out into the darkness. The flatness and the vastness produced a profound sense of release. I remember thinking, very simply, that there was a project in this, that emptiness itself could become the subject.

At art school I encountered the work of Bernd and Hilla Becher, whose industrial typologies demonstrated how seriality and repetition could transform the apparently mundane into something rigorous and compelling. Around the same time, I began looking more closely at the history of landscape photography from the mid-19th-century American tradition through to Australian photographers such as Peter Dombrovskis and Olegas Truchanas, and recognised that landscape photography could no longer rely on the “shock of the new.” In the digital age, novelty had diminished as a strategy.

The writer Edward Said described landscape not as a subject, but as a medium – a vehicle for carrying meaning. That idea clarified something I had already been intuitively pursuing. When I first encountered phenomenology, it was a philosophy that explained the underpinnings of the methods I had naturally lived and adopted. Rather than treating landscape as scenery, I understood it as a field in which perception unfolds, where light, space and duration become the true subject. The landscape functions as the medium through which emotional and psychological states are registered, particularly those that emerge through prolonged solitude and complete immersion over weeks or months at a time.

How did you first approach the landscape photographically, and how has your relationship to it shifted throughout your career?

I first approached the landscape in a relatively traditional manner. My early work was grounded in black-and-white film and informed by the formal clarity of the landscape tradition of the American West.

Over time, I became less interested in describing landscape and more interested in understanding how perception develops through duration. I began to notice that certain moments only became recognisable after extended time spent inhabiting a place, and that recognition itself was shaped by immersion. The decisive shift came when I chose to embrace space itself as the subject of inquiry. Working on salt lakes allowed the landscape to be reduced to an almost blank field, and the work moved away from topography toward perception itself. Light, tonality and scale became the primary elements. Landscape was no longer a subject to depict, but a space through which to explore duration, emptiness and the psychological states that emerge through immersion.

As the projects developed, my understanding of landscape broadened. I became increasingly aware that landscape is a human construct, and that it is never neutral. Even when appearing empty, it carries traces of memory and human presence. Rather than presenting landscape as untouched or exotic, I began to approach it as a complex field, one that shapes experience and is shaped by it.

You have had an ongoing relationship with Lake Eyre. What draws you back to it?

Lake Eyre has remained central to my practice because it offers a condition of reduction. Its vast flatness removes distraction and allows light, space and duration to become primary elements.

I initially thought I would visit only a few times. However, once a body of work was completed, a new question would emerge – a further “what if” that required returning. Each return gave rise to a distinct cycle within the broader project. The relationship became iterative rather than finite.

All the landscapes I work in offer the possibility of reduction, seriality and duration. This has shaped works such as Hector, the Greenland Icesheet project, and, in a different register, Blaze. The work develops through sustained attention rather than singular encounters.

Could you tell us about the interventions within the landscape that recur in your work – fire, mirrors, smoke – and how they connect with your broader themes?

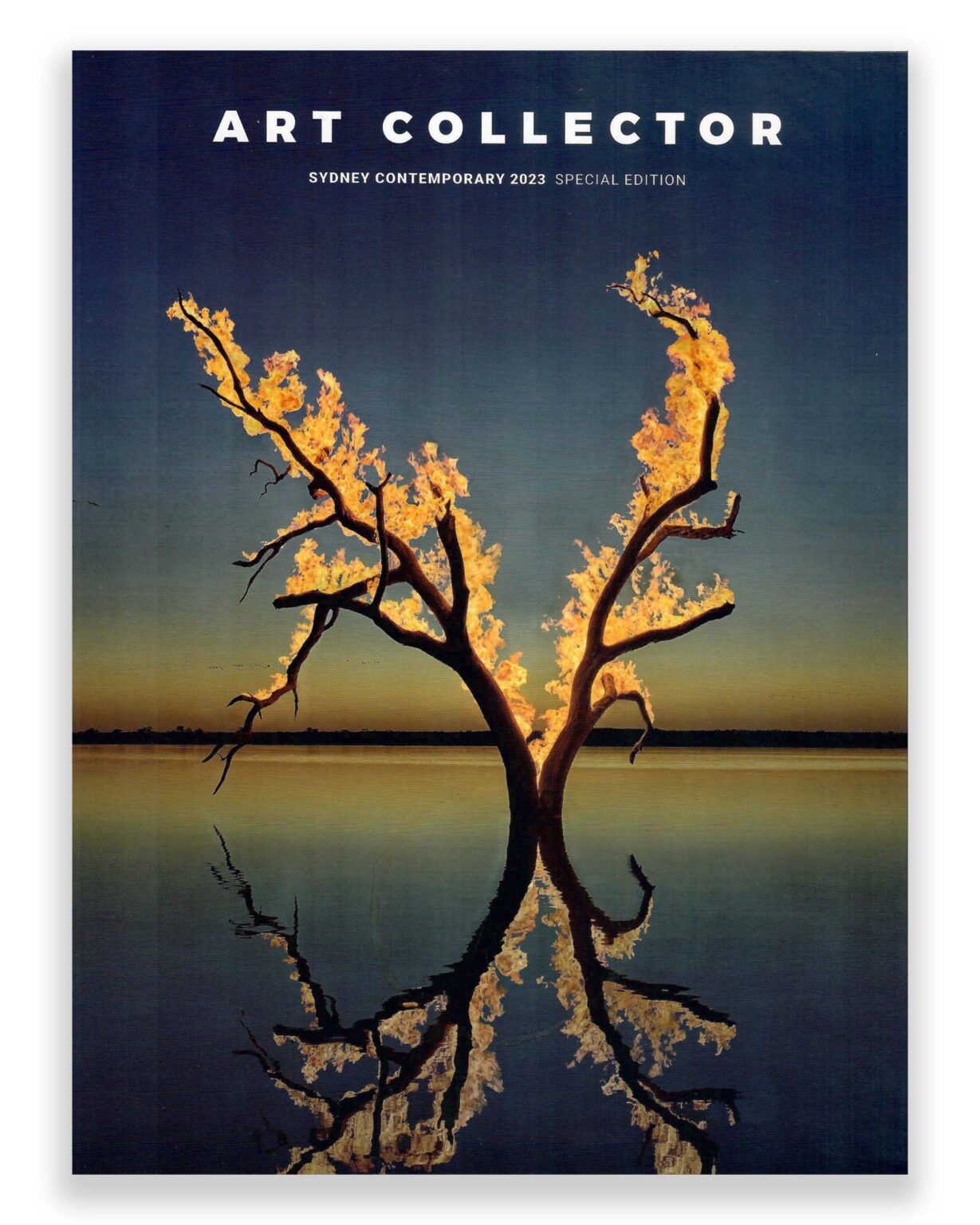

The interventions are intentional disruptions that alter how space is perceived. In Blaze, fire reorganises the field. The sites were chosen specifically because they were ephemeral landscapes – temporary bodies of water that exist only under particular conditions. Ephemeral waterways and lakes are a defining feature of the Australian inland. The flame operates in the same way: both are transient states that briefly permit a landscape to exist before vanishing.

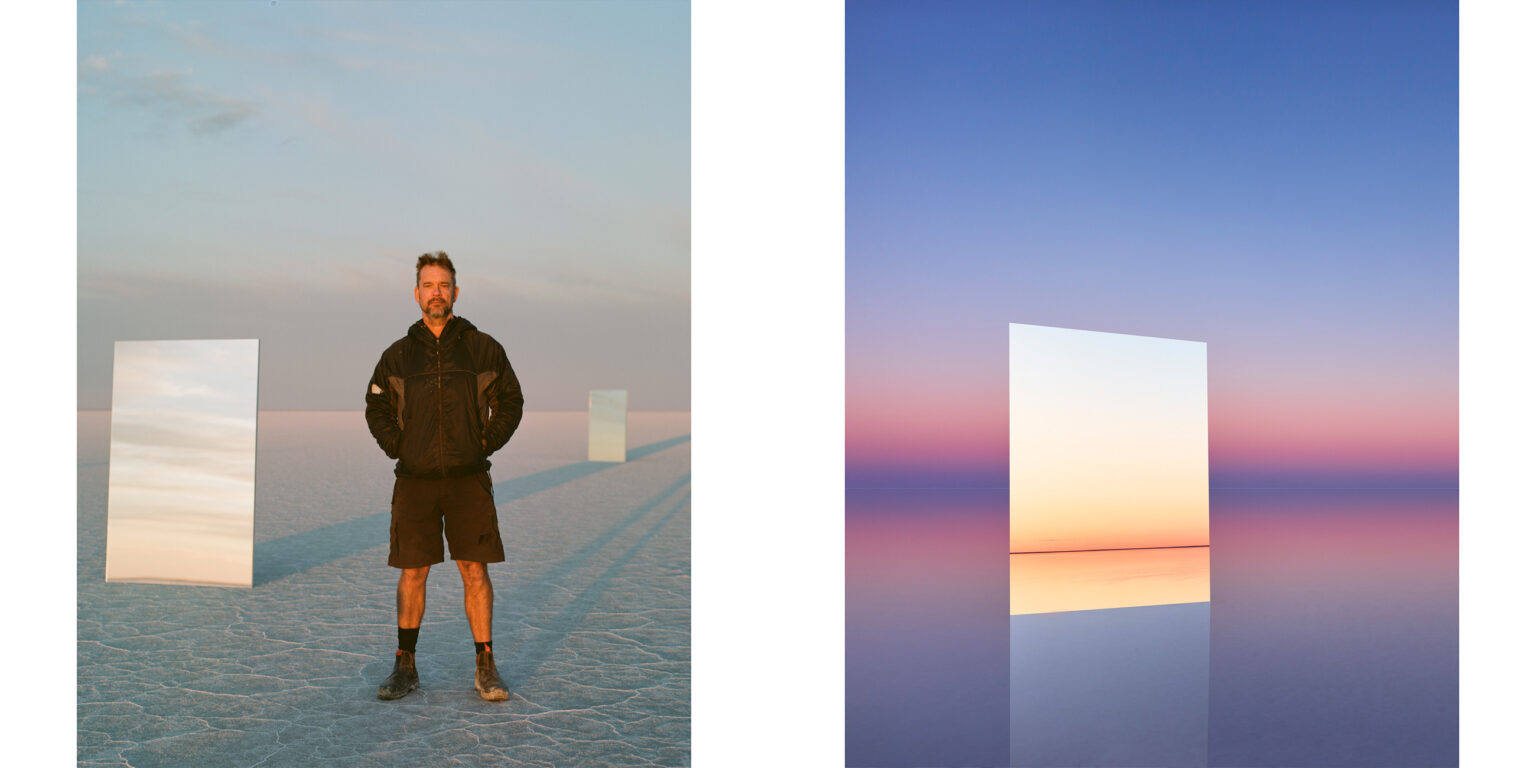

The mirror works operate through geometry and light. By inserting reflective planes into the landscape, I introduced a surface that absorbs and redirects the existing field. In the final image, the mirror ceases to read as an object and instead functions as a plane of abstraction. Horizon, sky and ground fold into one another, expanding the way the landscape can be read.

Time-lapse films are a part of your artistic practice, but there is clearly a temporal dimension to your still photography as well. What role do time and the durational aspects of your process play in your work?

Time is foundational to the work, whether in moving image or still photography. I have always been drawn to using the medium to make visible realities that sit just beyond ordinary perception. Time-lapse and long exposure reveal what is present but not immediately seen – shifts in light, weather and atmosphere, and the gradual movement of space itself. Time operates as a condition of immersion. Recognition does not arrive instantly; it emerges through duration. Time is not simply a subject of the work; it is the medium through which the landscape is understood.

Your body of work Salt unfolded over a 22-year period. Could you tell us about the development of that particular series and how do you look back at it as a project that spanned such a significant period of time?

I look back at Salt as the body of work that defined my process and methodology. It was never conceived as a long-term project. I initially imagined one or two visits; it grew into 31 visits over 22 years. It was three years and five trips in before the first exhibition works were made. During that period I was establishing a framework, a set of rules for how to work within that environment.

In the early years I camped at the edge of the lake and walked out each day, which was physically exhausting and consumed valuable time. Eventually I moved into the centre of the lake itself, transporting water and equipment by bike and trailer and camping for up to ten days at a time. That shift changed the work. The immersion became total.

At art school, my supervisor suggested I document the process on video. That material evolved into Salt, a 30-minute documentary commissioned by the ABC, which went on to receive international recognition, including Best Cinematography at Camerimage and an Academy Award shortlist. The moving image became an unexpected but integral extension of the project.

Technically, the series evolved alongside changing technologies. The early works were made on an 8×10-inch film camera, a formal, deliberate approach that established the project’s aesthetic. As digital systems matured, I began producing stitched panoramas to extend the field of view, and later night works that were not previously possible. The mirror works followed, then multiple mirrors, and eventually the merging of Salt and Blaze, where flame rose from the water’s surface. Each shift formed a discrete cycle within the larger project.

The lake itself imposed continual challenges. The most compelling conditions often occurred when rainwater lay in vast shallow pools across the salt. I would transport a picnic table on a trolley to create a stable platform. The salt, far more corrosive than seawater, required constant protection of equipment; mirrors demanded continual cleaning and polishing. Water sometimes had to be hauled across distances of up to 35 kilometres. Yet living alone on the lake was, paradoxically, peaceful and sustaining.

All of the physical and technical challenges were subordinate to the inquiry. The vision always came first. The duration of Salt was not strategic; it was the result of returning to unresolved questions. Each visit extended the framework, testing new conditions within a landscape that, despite its apparent emptiness, proved inexhaustible.

What were the starting points for your Hector, Icesheet (Greenland) and Blaze series, what were the challenges and ideas at play, and how do they each build upon the ongoing themes of your practice?

Hector emerged from the challenge of bringing a fixed, minimal frame to an unstable phenomenon, the large thunderstorm system that forms over the Tiwi Islands during the wet season. The starting point was a simple constraint: a repeated horizon line through which the storm would be observed. I established a jungle camp opposite the formation point and returned over multiple seasons, observing the daily life cycle of the storms. Duration and repetition were central. What interested me was not the surface drama of lightning, but the gradual accumulation of atmosphere, staying long enough for recognition of essential forms to emerge. The repetition of the horizon became a way of measuring instability, holding a volatile subject within a restrained compositional framework.

Icesheet (Greenland) was, in many ways, an extension of the Salt process. It pushed reduction further. Where Salt worked with crust, water and horizon, Greenland offered an almost total field of snow and ice. Atmosphere dominated the experience. Ice crystals suspended in the air bent and refracted light, creating subtle optical phenomena that became subjects in themselves. The landscape was defined even less by form than Lake Eyre, and more by the behaviour of light within it.

At the same time, the abandoned Cold War missile detection stations DYE-2 and DYE-3 introduced a contrasting condition. The radome structures and traces of mundane habitation sat within what felt like a void inside a larger void. These architectural remnants became the basis for both large-format still works and a three-channel video installation, created in conjunction with composer Tom Schutzinger, who worked at the station in isolation with me over the course of a month. The project was logistically difficult; weather frequently prevented work from commencing. On one visit, a journey across the ice sheet was undertaken by dogsled with a team of local Inuit, later forming the basis of the feature documentary Nothing on Earth, commissioned by the ABC.

Blaze marked a shift from observing unstable conditions to introducing a controlled intervention. The work was situated within ephemeral and fragile inland river systems. These were temporary landscapes that appear briefly under specific conditions before receding again. The flame was generated through concealed, flexible gas lines wired along the backs of the trees in a sculptural line that outlined their form. The intervention was carefully managed and non-destructive, designed to exist only for the duration of the image. Like the waterways themselves, the fire was temporary. Both were transient states that briefly defined the landscape before disappearing.

The starting point was to test how a volatile element might reorganise a reduced field. Fire altered scale and horizon, creating a momentary alignment within an otherwise minimal environment. In this sense, it shared a logic with Hector, working with a volatile subject within a restrained frame, but here the instability was introduced rather than observed.

How does your work in film and commercial photography influence aspects of your fine-art practice?

I was an artist first. The commercial and film work evolved out of the ideas and methods established in the fine-art practice, rather than the reverse.

The long-term art projects required making images from subtle gradations of light and colour, often realised at large scale. That demanded technical precision and the use of large-format systems. Technical capacities, including time-lapse and complex exposure techniques, were developed in response to artistic questions and later translated naturally into film and commissioned work.

Are there landscapes you’re yet to visit that would be interesting for you? What other projects are you looking forward to?

There are many landscapes that are conceptually and visually compelling. At this stage, I am focused on testing ideas, including ways of working with multiples and layered durations. The direction is still forming, but it continues the same inquiry into scale, perception and time.