MICHAEL REID BEYOND

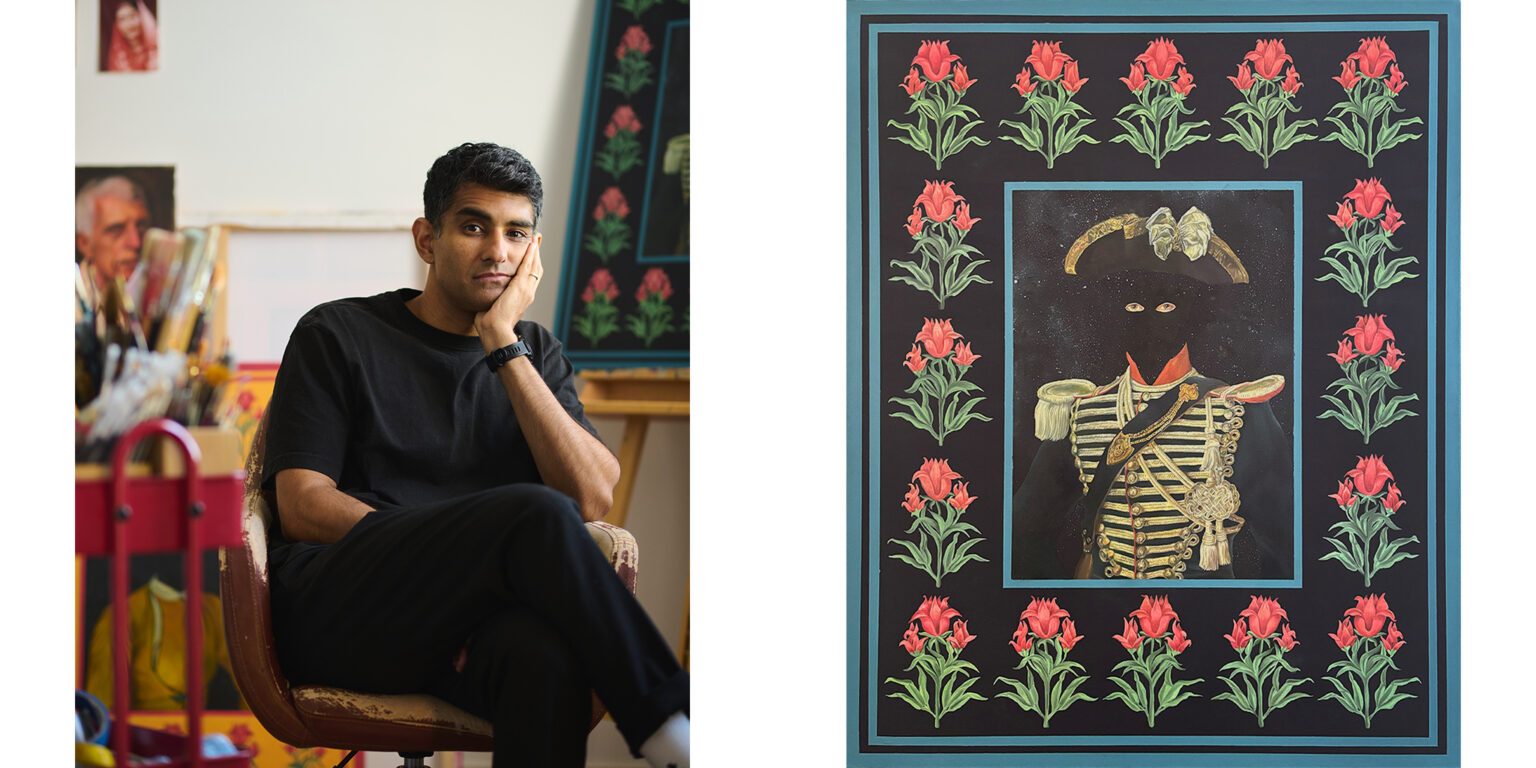

Sid Pattni

ARTIST PROFILE

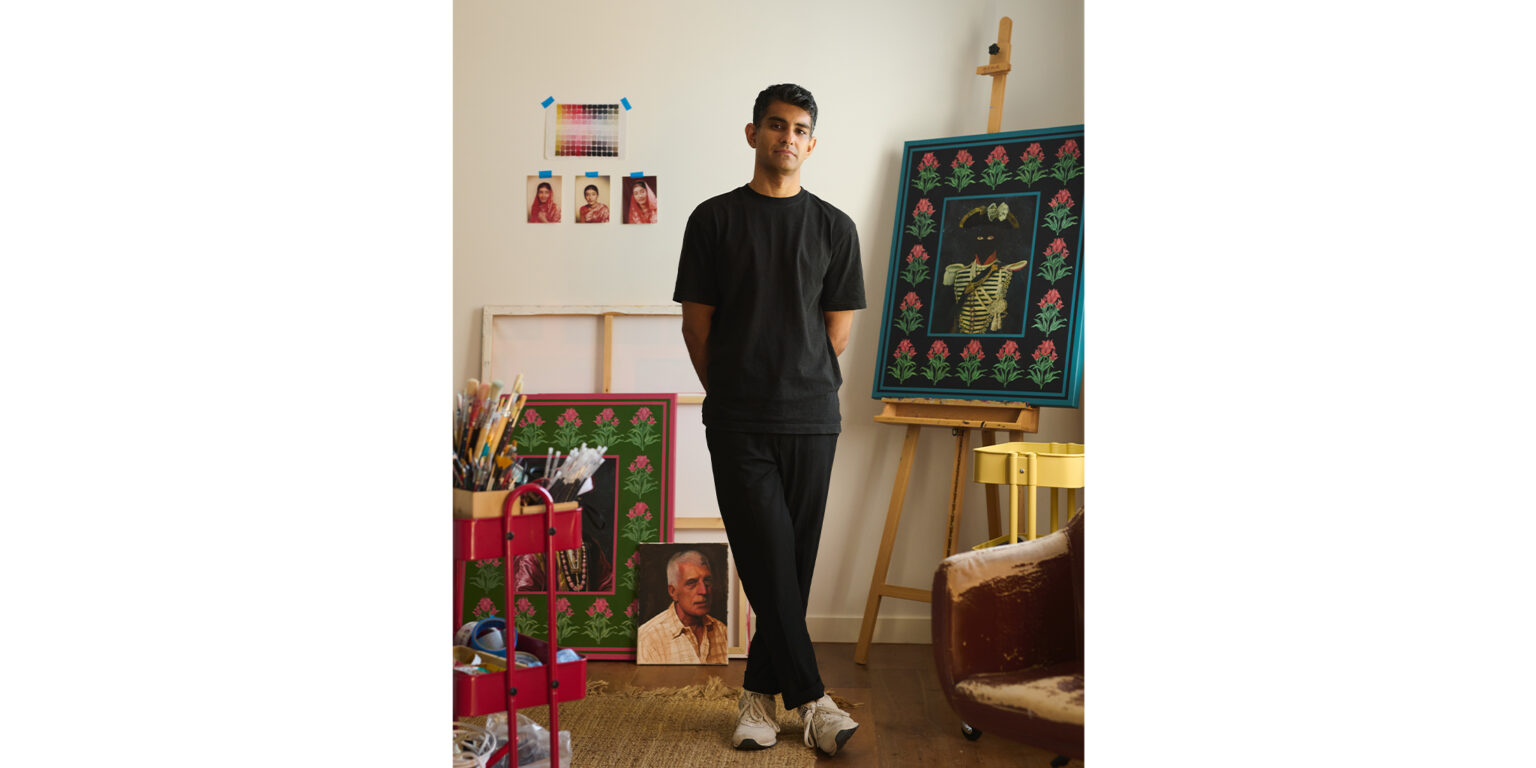

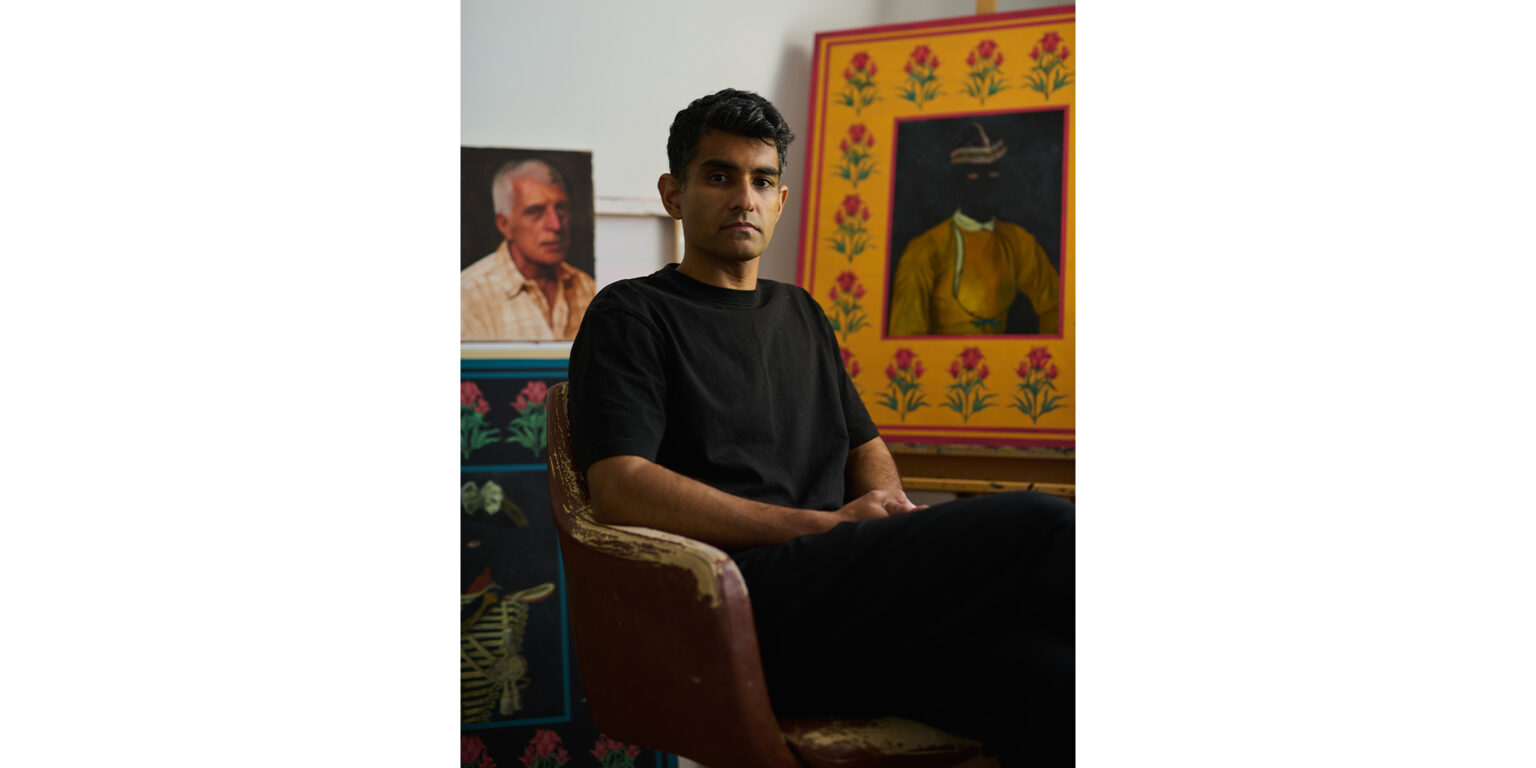

Sid Pattni is an Australian artist of Indian descent whose work unpacks the intricacies of identity, culture and belonging within a post-colonial framework. Born in London, raised in Kenya and now based in Naarm/Melbourne, Pattni aims to contribute to the ongoing discourse surrounding art and its role in communicating the complexities of diasporic identity.

Working primarily in painting and embroidery, Pattni was awarded the Kennedy Prize in 2023 for his portrait of Mostafa “Moz” Azimitabar and was shortlisted for the 2024 National Emerging Art Prize. In May 2025, he was named a finalist in the Archibald Prize for Self-portrait (the act of putting it back together) – his first shortlisting for the Art Gallery of New South Wales’s flagship program and one of the country’s most prestigious and closely watched cultural accolades.

Following this significant career milestone, Pattni will present his first solo exhibition with Michael Reid Sydney in July 2025. On the eve of our announcement of the artist’s representation by Michael Reid Sydney + Berlin – and as he completes a new body of work for his Michael Reid exhibition debut – we visited Pattni’s Melbourne studio to discuss the ideas and influences that propel his practice.

Read our interview with Sid Pattni below. To receive early previews and priority access to his forthcoming series, please email danielsoma@michaelreid.com.au

What were some of your earlier artistic influences? How do they continue to inform your painting practice?

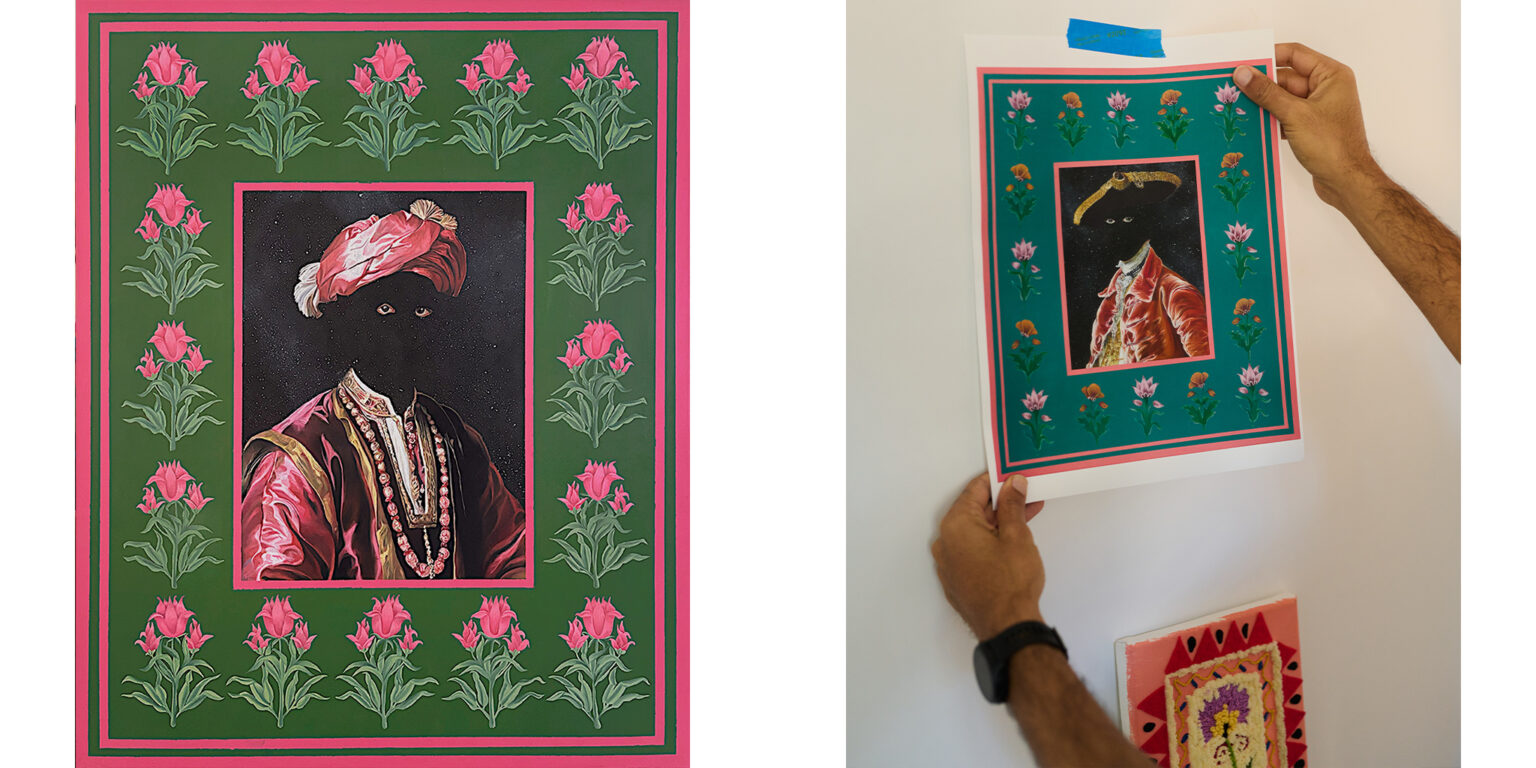

Growing up between cultures, I was surrounded by rich but conflicting visual languages – everything from Bollywood posters and Indian textiles to the Western art we studied in school. Early on, I was drawn to the intricacy and symbolism of Indian miniature painting, but it wasn’t until much later that I understood its colonial entanglements. These influences still underpin my practice today. I’m interested in how aesthetics shaped under empire can be reclaimed and reconfigured to tell new stories – stories about migration, memory and identity.

What initially drew you to painting? Are there themes, references or approaches that you returned to?

Painting became a way to process the dissonance I felt as someone navigating multiple cultural identities. Over time, I’ve returned again and again to themes of hybridity, belonging, and erasure. I often reference historical visual formats – Mughal miniatures, Company paintings, colonial portraiture – not as homage, but as a means of critique and reimagining.

What have been some of your favourite career experiences?

Winning the Kennedy Prize for my embroidered portrait of Mostafa “Moz” Azimitabar was a powerful moment, not just because of the recognition, but because it felt like an artwork that truly honoured someone’s story and resilience. Another major milestone was The Story of Us project, where I merged painting with oral storytelling from former refugees. That intersection of visual and auditory storytelling deepened my understanding of what art can do: it can hold space, provoke empathy, and reframe narratives that are too often simplified or ignored.

What are some of the ideas and experiences that have informed your more recent work?

My most recent work continues to investigate the long shadow of colonialism on diasporic identity. I’ve been particularly focused on how external projections – constructed through orientalism and the colonial gaze – have been internalised by communities, including my own. The National Emerging Art Prize work and my upcoming show at Michael Reid Sydney explore these ideas through composite visual languages: Mughal miniature structures, British botanical drawings, and faceless figures. These paintings are a response to inherited ways of seeing, but also an invitation to look again – more critically.

Could you tell us about Self-portrait (the act of putting it back together), which has been shortlisted for the 2025 Archibald Prize?

The Archibald piece started as a meditation on what it means to be seen – particularly when my identity has often been misrepresented or erased. I leaned into the tropes of historical portraiture but stripped away my face, retaining only the eyes and garments. This removal of identity isn’t about anonymity; it’s about reclaiming the gaze and disrupting traditional power dynamics in portraiture. As I worked, the painting became more introspective – it evolved into a conversation between the viewer, myself, and the histories that sit between us.

Could you tell us more about the series you are working on for your upcoming exhibition?

The July exhibition at Michael Reid continues my engagement with colonial visual traditions. The floral borders, inspired by British botanical illustrations, are no longer literal – they’re invented, composite, almost dreamlike. They symbolise how cultural artefacts were appropriated and re-contextualised during empire, and how these reinterpretations continue to influence diasporic self-perception. What feels new in this body of work is a deeper emotional intensity.

Photographs by Tim O’Connor.