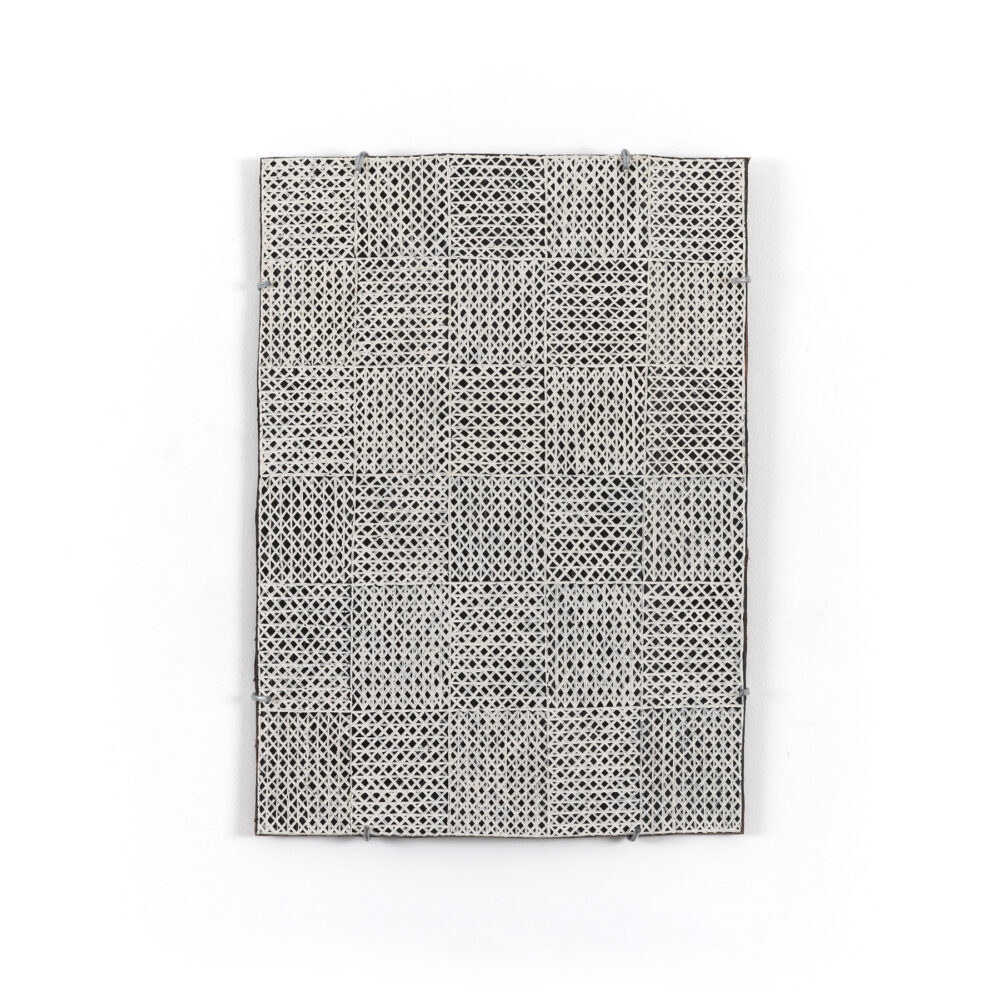

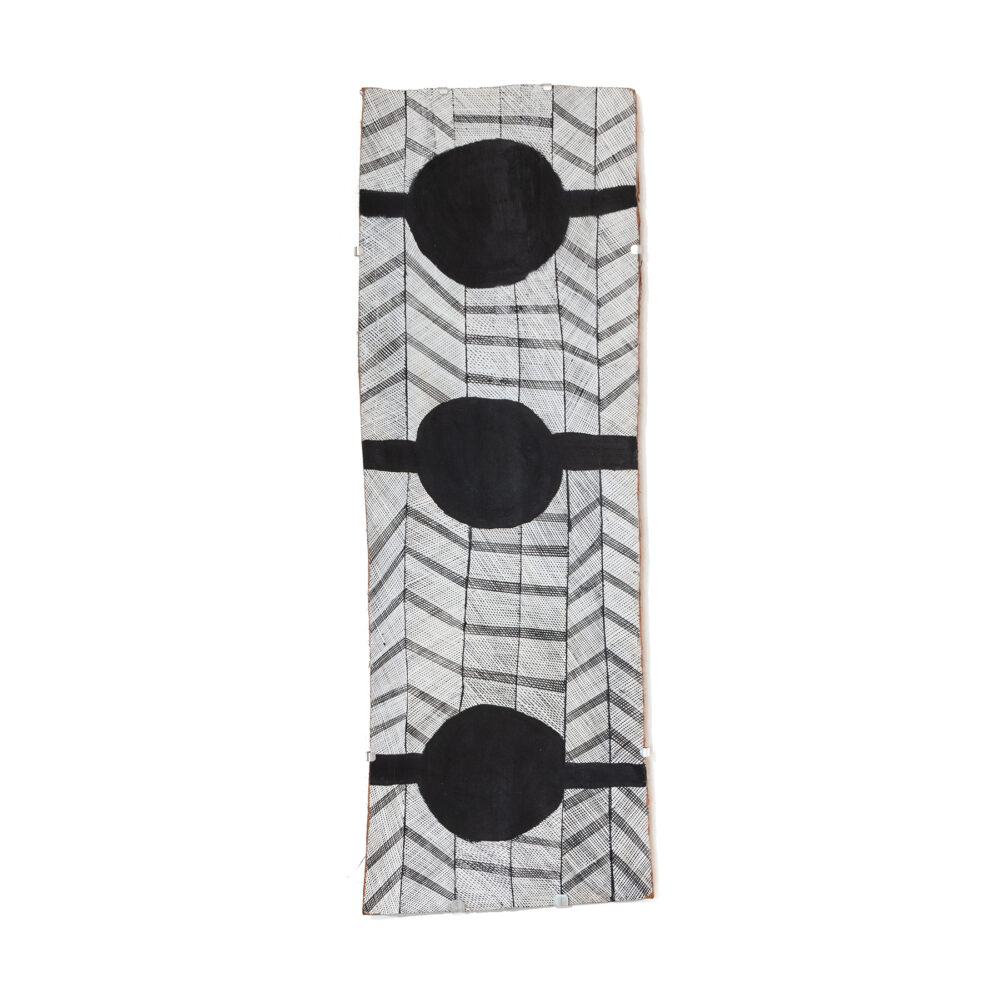

Michael Reid Sydney + Berlin is thrilled to announce the arrival of the most expansive and spectacular sculptural installation to date by Dharawal/Bulli-based multidisciplinary artist Mai Nguyễn-Long, whose monumental room-sized work The Vomit Girl Project is now showing at QAGOMA as a centrepiece of the 11th Asia Pacific Triennial of Contemporary Art.

With this towering achievement, Nguyễn-Long stands at the forefront of a global assembly of 70+ leading contemporary artists, collectives, makers and thinkers from more than 30 countries whose new and specially commissioned work is now lighting up the latest chapter of QAGOMA’s flagship program.

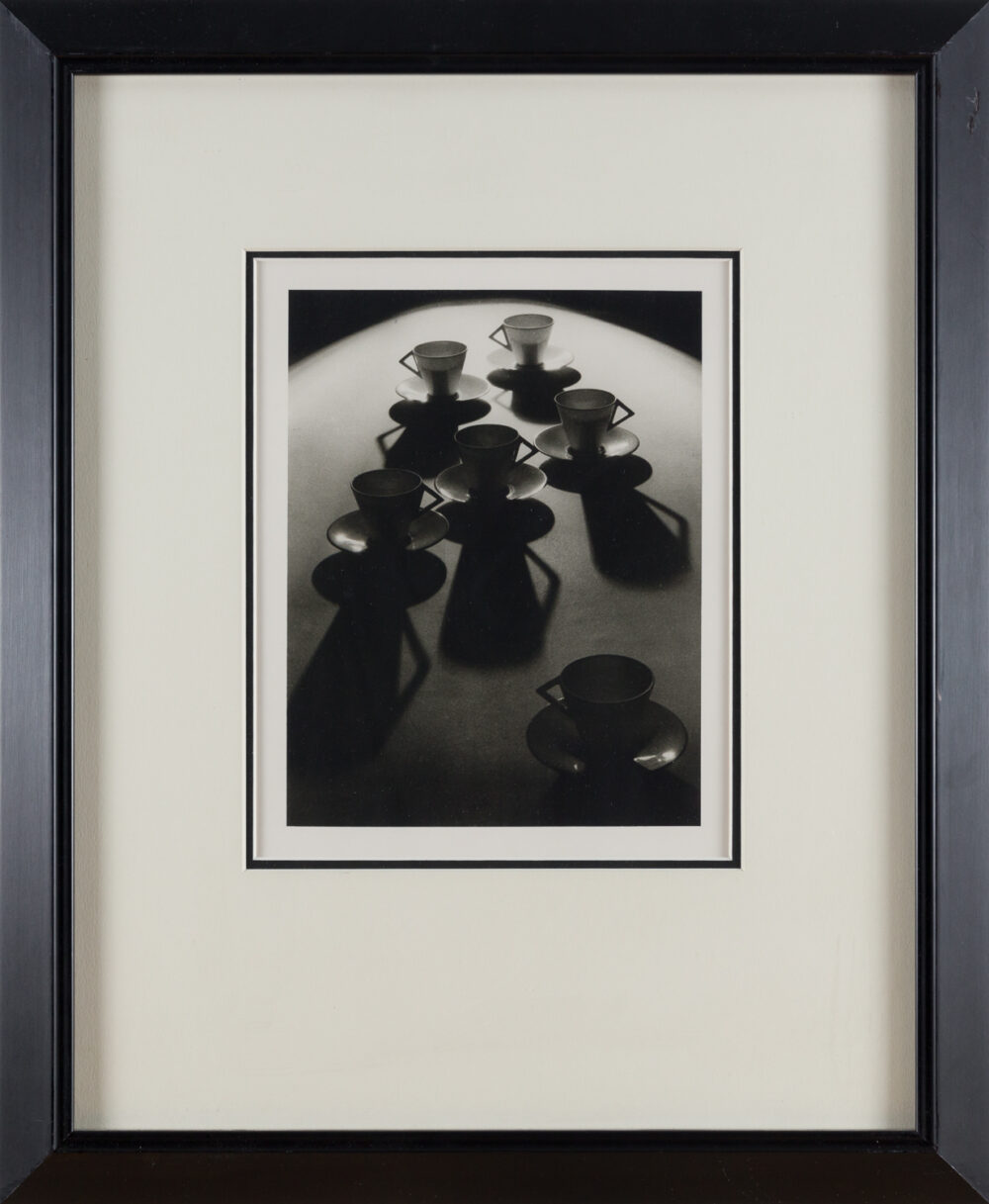

To celebrate the opening of APT11, we are pleased to highlight a selection of sculptures from The Vomit Girl Project that can already be viewed and acquired online, and we invite those interested in additional works from Nguyễn-Long’s epic QAGOMA installation to please contact a gallery representative.

“Vomit Girl has a whimsical, playful side informed by concepts of mistranslation, wordplay and idiosyncratic readings of Vietnamese folklore,” writes QAGOMA’s Associate Curator of Asian Art, Abigail Bernal, in the catalogue essay accompanying The Vomit Girl Project.

“Nguyen-Long describes her Vomit Girl sculptures as ‘contemporary folkloric forms’. In the artist’s words, they emerge from the proposal that contemporary art can draw from folkloric strategies to open up spaces for suppressed, hidden and new stories to emerge beyond diasporic trauma.”

To discuss works from The Vomit Girl Project and receive priority access to upcoming releases from Mai Nguyễn-Long, please email danielsoma@michaelreid.com.au