In the lead-up to the announcement of Tim Maguire’s representation by Michael Reid Sydney + Berlin, the gallery team sat down with the artist for a wide-ranging conversation exploring the ideas, processes and optical tensions that have shaped his internationally acclaimed practice across a career spanning close to four decades.

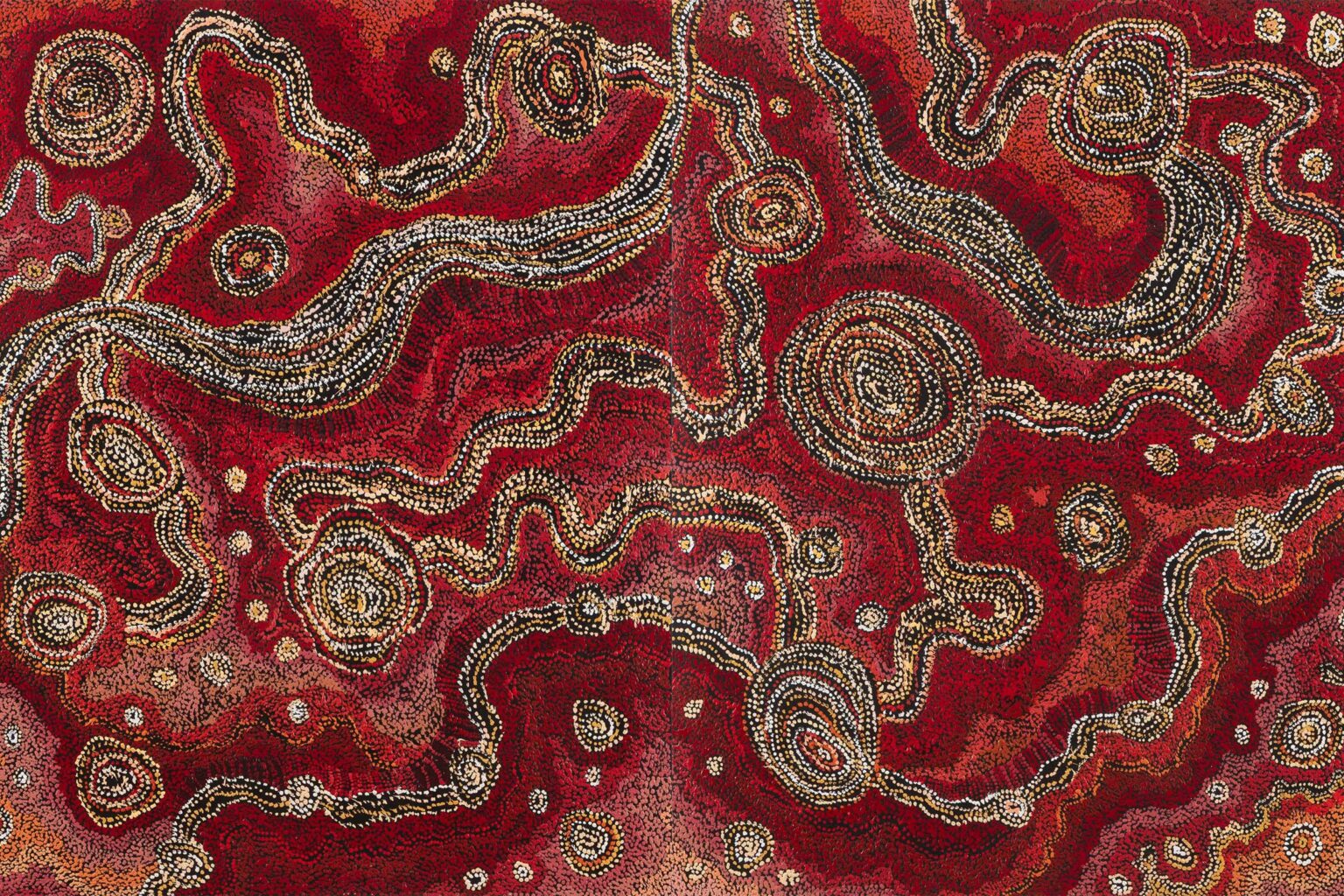

“No matter how naturalistic a painting appears, it’s still just a physical accumulation of paint on a surface – and yet we bring so much to it as viewers,” says Maguire. “I was always trying to make paintings where that tension becomes evident: where you think, ‘This really is just a whole lot of gloopy paint,’ and at the same time, from across the room, it looks like a photograph.”

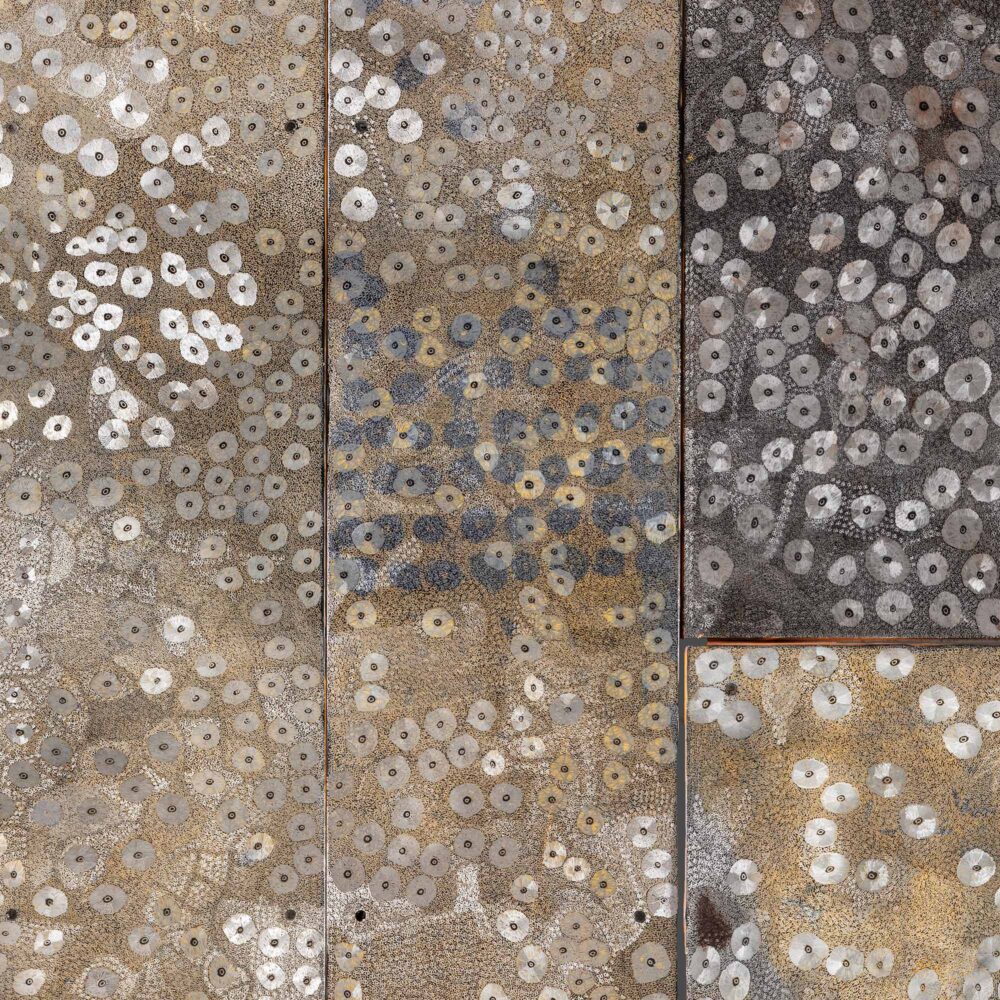

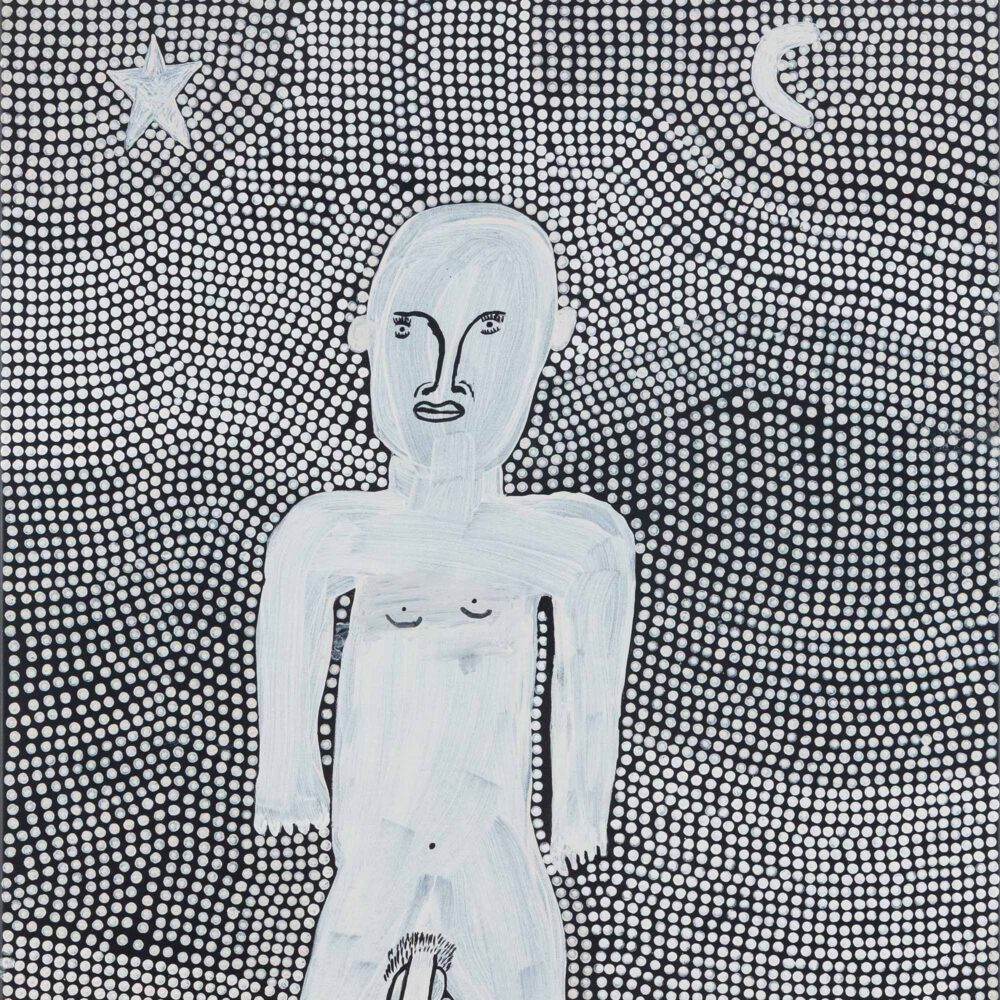

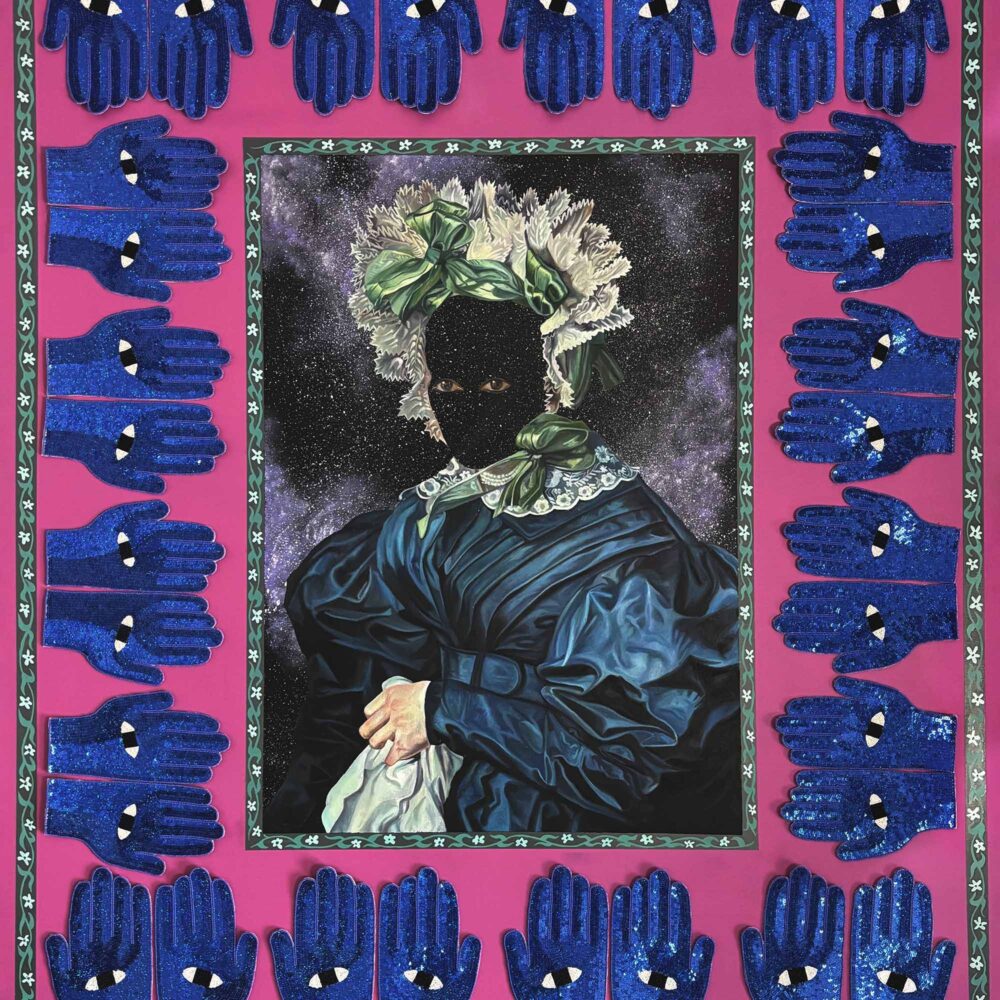

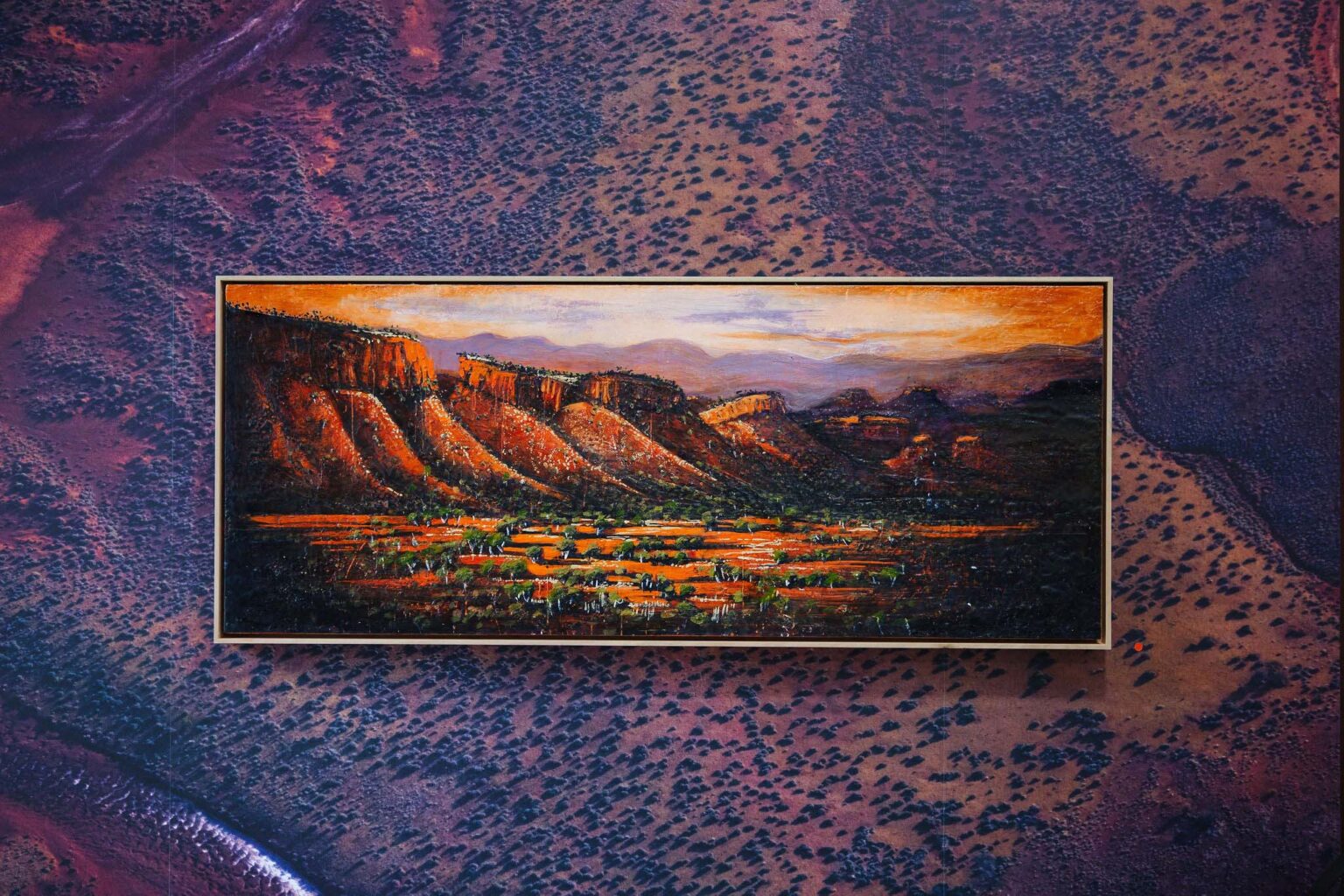

Read the full conversation below alongside a curated selection of recent paintings by the artist, newly available through Michael Reid Sydney + Berlin.

For enquiries, please contact dean@michaelreid.com.au

“There’s a play between the illusion of the image and the physicality of the paint. The ideal painting for me is one where, up close, you see nothing but paint and process and layers, and then, from far enough away, the whole thing resolves into a convincing illusion.”

TIM MAGUIRE

___

Your practice has encompassed various mediums across your career. How do you approach these distinct facets of your practice – painting, printmaking and photo-based work – and how has moving between different fields become embedded within your painting process and shaped your broader thinking about image-making?

I’m primarily known as a painter, but I see printmaking as being of equal importance in my practice. That’s not necessarily represented in the way my work is seen, because there aren’t always the same opportunities to show the prints. But I do make a lot of prints, so it’s an ongoing practice.

It started in 1987, probably. I’d already begun exhibiting – my first solo show was in ’84 – but it was a kind of revelatory moment. I found myself working with a master printer who explained that you could build up colour through discrete layers of primary colour – yellow, red, blue, black – and that you could achieve a full spectrum through those few colours. The idea of working with transparent inks on white paper, and allowing the whiteness of the paper to illuminate the image and create luminosity, was a revelation.

I made a few prints with the Australian Print Workshop in those early days, but I also took those printmaking ideas back into the studio. I started thinking, can I make paintings in the same way? That’s when I began working with transparent colour – not so much in strict layers, but using transparency and the whiteness of the canvas to illuminate the image. Thin glazes and transparent pigments came directly out of printmaking.

It was only some years later, when I stumbled across a process of splashing solvent into the colour layers to remove parts of each layer in a fairly random dot pattern, that I realised I could emulate the quality of pure points of colour sitting side by side. That led to my colour separation paintings – which, of course, is a printmaking term.

Could you tell us about the colour-separation process – how has it developed across different bodies of work?

When I got to the point where I realised I could actually do it, the splashing of the solvent was a key component and quite random. I wanted each layer of colour to remain visible as an independent entity – to reveal the process itself. It was about the idea that you could make an image by pulling it apart and putting it back together again.

To do that, I needed to work quickly. It might be a four- or five-hour painting session, then splashing the solvent while the paint was still wet enough to react, but dry enough not to collapse into a mess. Timing was everything. I liked the idea that the image was brought together through a mechanical process largely determined by chance – how much solvent comes off the brush, how dry the paint is. The image comes together almost magically, which, for me, was one of the great attractions of printmaking.

Later I realised – particularly after a series of massive paintings in 2000 – that this approach had limits. Those works were about two-and-a-half metres by six metres, and I ended up needing serious physiotherapy. So I slowed down. It wasn’t essential to do everything in one session, and that allowed for more control. There’s a desire to master the challenges you set for yourself, and eventually you do.

In this process, any colour might be a combination of yellow, magenta and cyan. Gauging that while applying it is almost impossible. Often it’s only when you apply the third colour that you realise you’ve gone wrong with the first two. Those pitfalls are what keep it interesting. I’ve got to the point now where I’m pretty good at navigating them, so maybe it’s time to do something else. The last two shows I did were very ambitious, large diptychs. I could never have done those 25 years ago. It felt like the end of something.

You spoke about holding the image in a state of becoming – the work being less about representation and more about ‘imageness’ in a slightly dispassionate way.

For sure. It was coming out of postmodernism, and the idea that images were floating around – you could grab one from here, one from there – like slides on a screen, which is how we learned about art back then.

I was trying to make paintings that looked like that. They were flat, transparent, with no tactile physicality. The paint was a very thin veil – almost like a luminous projected image, closer to a cinema screen than a physical object. The images could be anything. The weirder the colour combinations, the better. I moved between representational and abstract things, and the common denominator was process.

There is a physicality to the way your paintings are experienced – both in their monumental scale and in the way a picture might cohere at a distance or dissolve into abstraction up close. How do you consider scale in the making of a work?

That transformation is really important. I always thought the great thing about large-scale works was that you could be incredibly loose at the coalface, and yet, if the viewer stepped back far enough, the image could come together.

There’s a play between the illusion of the image and the physicality of the paint. The ideal painting for me is one where, up close, you see nothing but paint and process and layers, and then, from far enough away, the whole thing resolves into a convincing illusion.

Ideally, the viewer is like a rubber band – moving back and forth between those two states. For me, that tension is the magic of painting. No matter how naturalistic a painting appears, it’s still just a physical accumulation of paint on a surface – and yet we bring so much to it as viewers.

So I was always trying to make paintings where that became evident: where you think, “This really is just a whole lot of gloopy paint,” and at the same time, from across the room, it looks like a photograph.

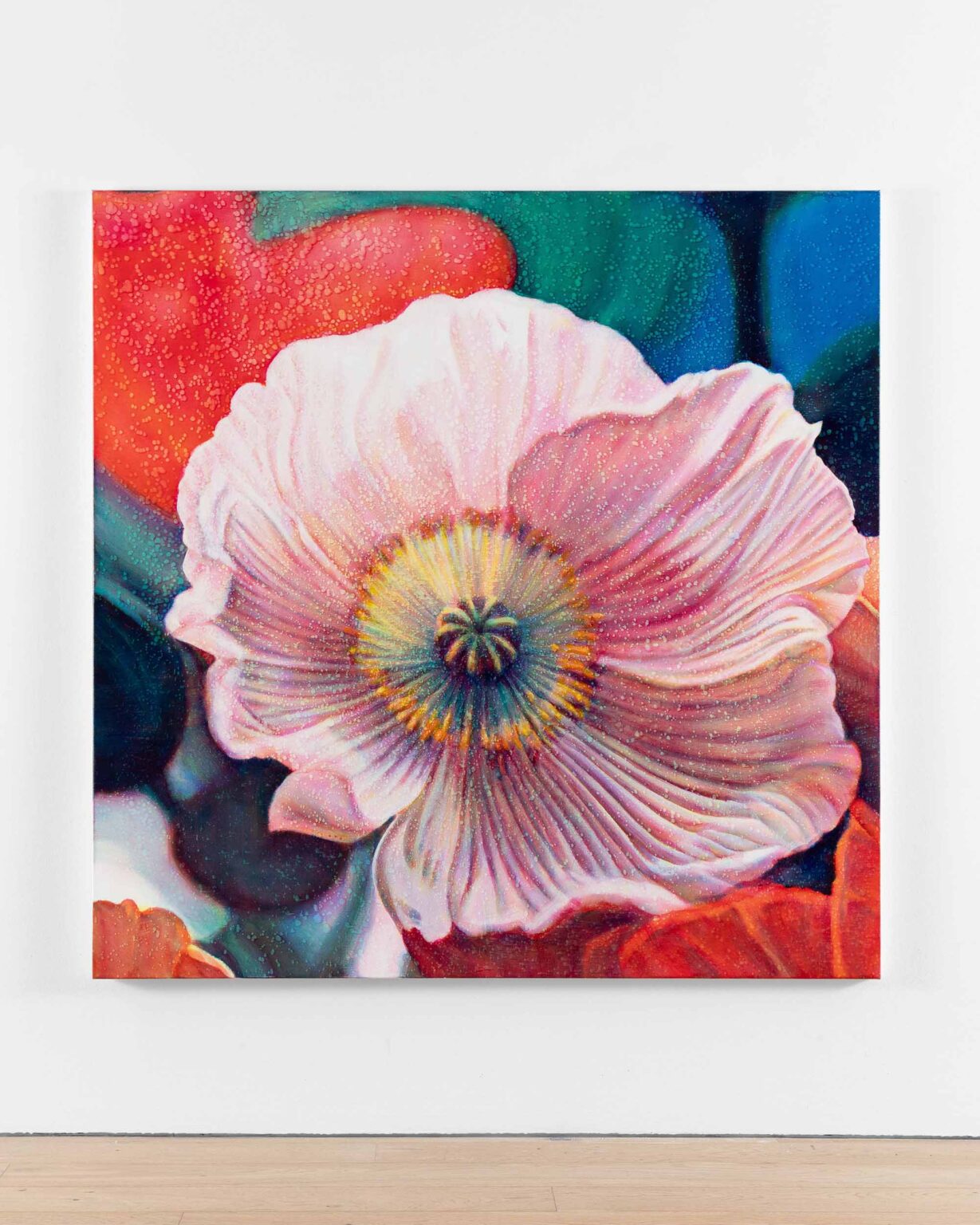

That sense of scale – of cropping and extrapolating source imagery into something cinematic – also transforms the subject. How do you think about beauty in your work, particularly when it’s pushed to extremes?

It’s tricky, because even to say your own paintings are beautiful sounds vain or arrogant. For a long time there was an idea that aspiring to beauty was philosophically flawed – that it smacked of elitism or privilege – so it’s hard not to have an ambivalent relationship with it. But if I look across my work, the aesthetic quality has always been a strong driver. It’s about creating an image that holds your gaze long enough for it to start working on you. You begin to see it differently.

We’ve all had the experience of hearing a song for the first time and feeling nothing, then loving it the fiftieth time. That’s hard to achieve with painting. We’re less and less trained to spend time with images now. So beauty can be a way of slowing the viewing process.

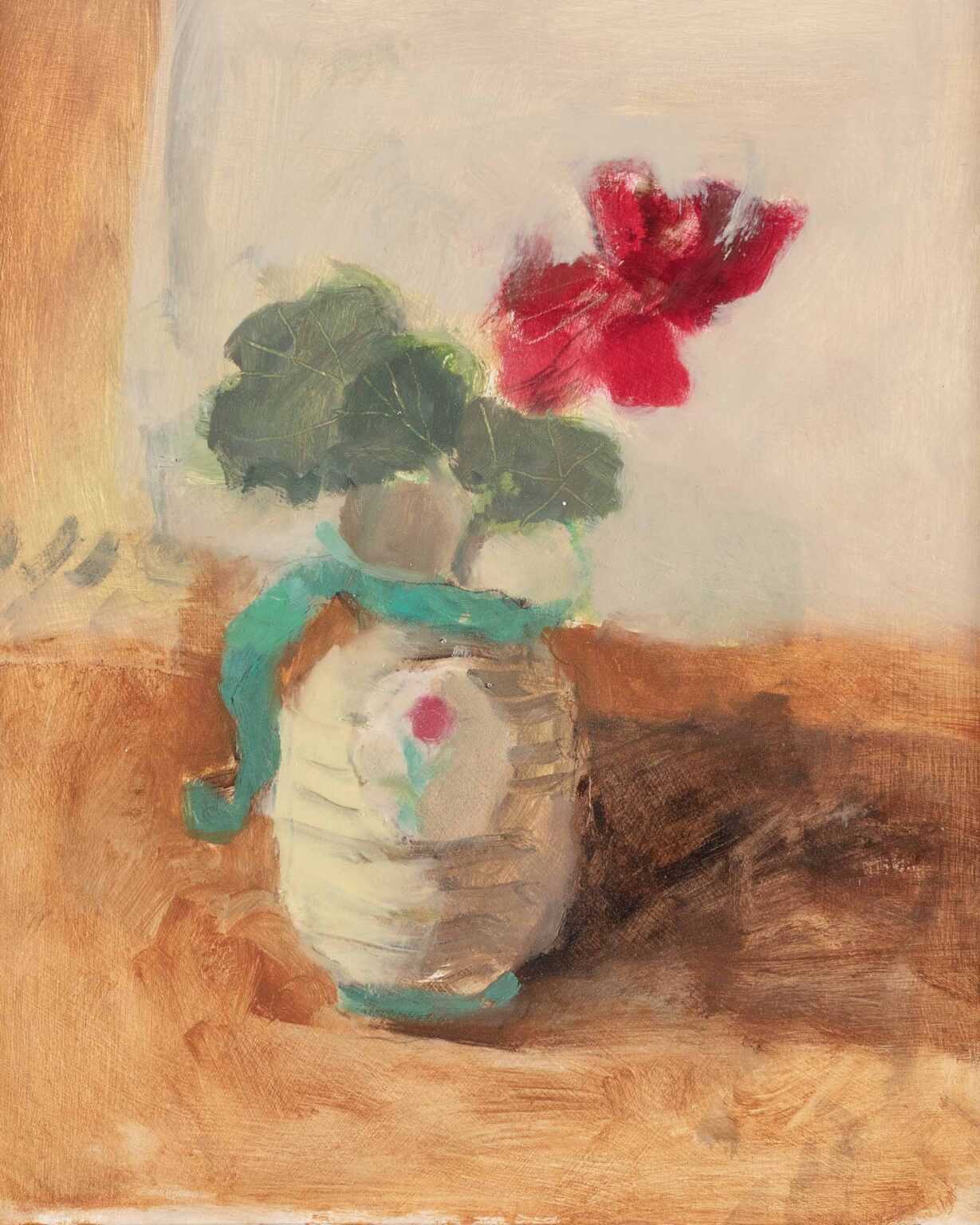

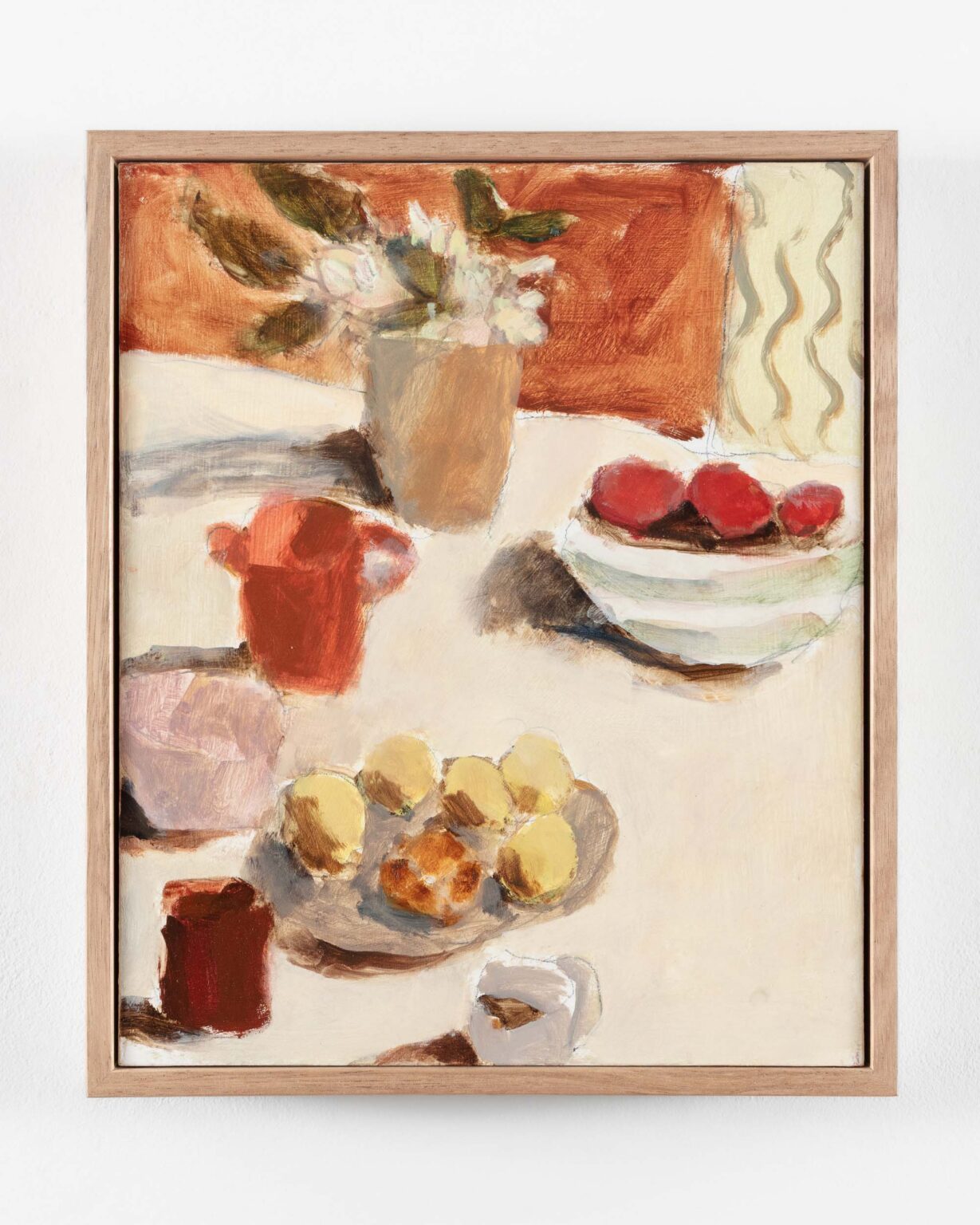

Flowers were annoying in that sense, because everyone assumes flowers are beautiful. I wasn’t interested in prettiness. What interested me was the tradition – the philosophy behind Dutch still lifes, mortality, fleetingness. You could also zoom into a flower and find forms that were almost abstract – curves and dramas you wouldn’t find in a portrait or landscape. They had no top or bottom. They had the vigour and thrust of something like a Delacroix – writhing, energetic. Yes, they were flowers, but that wasn’t really the point.

I don’t really think about beauty per se. I see something in the world and think, I’d like to photograph that. Then I see something in the photograph that makes me think it could become a painting. Sometimes you get nothing. Sometimes you get something unexpected, and that can open up a whole new series.

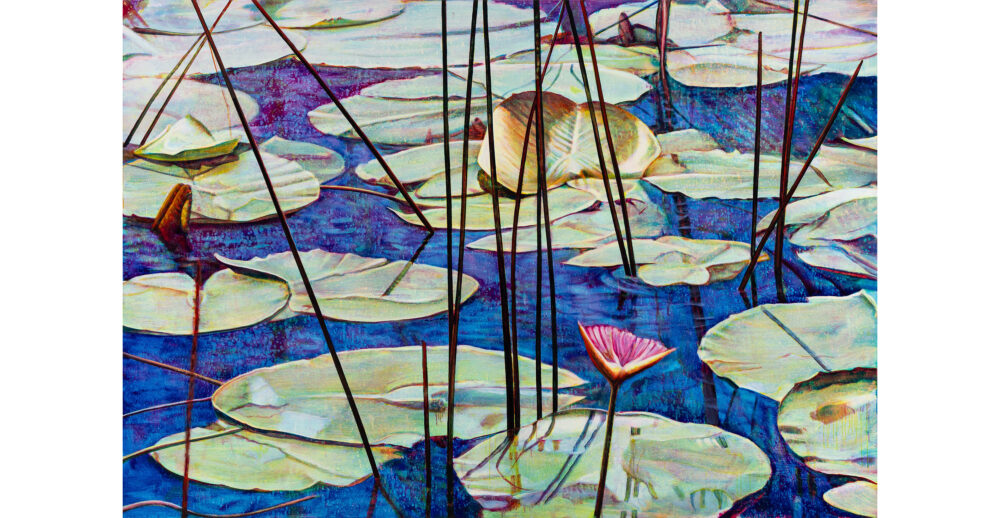

One of the big things in my work is the relationship between the abstract and the illusionistic. Monet’s water lilies are a good example. They’re almost abstract, but there’s a sense of space that’s both perspectival and flat. You never see the horizon. That contradiction is what painting is. You read space, but the surface is flat. Two contradictory things at once. It’s like life. There’s no logic to it.

Your career has unfolded alongside a broader shift from analogue to digital. How has that transition influenced your thinking about images and surfaces?

Even early on, if I was taking a detail from a Dutch still life, it was already an image that had passed through multiple stages. By the time I found it, the painting was 300 years old. It had been photographed, reproduced in a book, sat around for decades, then scanned – and from that fragment I was making this huge painting.

The idea of moving from analogue to digital and back to analogue – the oil painting – felt very comfortable. The same applied to photographing, manipulating images digitally, printing them out, then using them as the basis for paintings or lightboxes.

If I painted the same image three times as colour separations, they would all end up different; I’d never make two the same.

Around that time, digital photography was emerging. I went to New York and came back with a Kodak digital camera. Early digital images had strange effects – colour fringes, glitches – which I found fascinating. The question became how to translate that into painting. That’s where colour separation came in.

It creates a glowing quality. With opaque paint, light bounces off the surface. With transparent pigment, light passes through, hits the white canvas, and comes back out – like stained glass. So it might look like a painting of a flower, but really it’s a painting of a photograph of a flower. There was always a distance between me and the so-called subject.

With recent series such as Small Worlds and Lost and Found, you returned to Dutch floral still lifes as source material. What prompted that return?

That was partly about accessibility. In the early 1990s, I was working from postcards or the occasional book. Now museums have incredibly high-resolution images you can zoom into endlessly. Suddenly there was all this material available, and I had the technical capacity to deal with it.

Earlier, I liked not knowing what I was painting. The fuzzy postcard freed me up. It was just shapes and marks. I didn’t know if it was a leaf or background, and I liked not knowing. Now it’s very clear what it is, and I’m interested in it. I really enjoyed painting the little bugs and strange minutiae that had been scrupulously recorded 400 years ago.

These series seem to involve a more explicit engagement with the symbolic allegorical aspects of Dutch still-life tradition. Do you feel there was a shift? And what felt newly available to you in drawing out those narrative layers?

I don’t know if it’s maturity, but I stopped denying the source. For a long time I talked about the work as being about process. Now the process is a given.

There’s a paradox in Dutch still lifes. They were moral reminders of mortality – a reminder that beauty fades and you end up a skull. At the same time, these paintings have been preserved for hundreds of years. They’re frozen under varnish. They’re about life and its fleetingness, but they’re also kind of dead. I was trying to make loose impressions – bigger, more fluid – to almost revivify them. To release them.

There had also been terrible bushfires just prior, and that was all happening around the time of COVID; this idea that tiny viral agents could turn everything on its head. Bushfires have been a theme in my work for a long time. They’re illustrations of the fleeting, unreliable nature of existence.

Beauty is subject to those forces. Nothing is timeless or universal. There’s a resonance between those ideas and what underpinned Dutch still lifes originally. So I was happy to re-dock my boat there, with more attention.

This openness to narrative feels especially present in bodies of work such as Old World, New World and Regeneration, which responded to the Kinglake bushfires. How did those works take shape?

Bushfires had been part of my thinking since art school. I grew up in the Blue Mountains – they were an ever-present danger. You felt safe, but the wilderness was always there. I made early works about that contrast – everyday life set against an underlying threat. A barbecue in an empty space, sausages frying, bushfire smoke on the horizon.

After the Kinglake fires, I took panoramas of the burnt landscape. The twisted branches looked almost nuclear, but in the foreground there was vivid green regrowth. That energy of renewal after such ferocity was incredibly striking. That became the source material for the Kinglake works images – mainly large prints and light boxes, though I’ve also made some paintings from it.

The Kinglake works introduce elements such as falling ash, which, like the cascading snow in your wintry paintings, bring another optical layer to the image. How do these motifs operate for you?

It was an extension of my fascination with the luminous quality of the digital screen. I was making images on screen, printing them large, but there’s always some loss. Printing onto backlit screens maximised that luminosity.

More recently, I revisited canvases of falling snow. I superimposed imagery from the Kinglake photographs – trees and branches – in a way that integrated the snowflakes into the space. The juxtaposition of burnt bush and snow gave the works a strange quality. In paintings where I’d used colour separation, the red, green, and blue snowflakes looked like flying embers or spirits – something ghostly or magical. They refract light, almost like prisms, and can act like little lenses that reveal the forms behind them.

You divide your time between rural France and Australia. How does that movement shape the work?

People in Australia say my work feels European, and people in Europe say it feels Australian. So I’m somewhere in between. I might work on a painting in one studio and finish it in the other, and it looks completely different. The light does have an effect – you see things differently. You adjust, you accommodate.

But I’ve never really consciously thought, “That’s a European thing, that’s an Australian thing.” The gestation period is so long that when I’m in France, I’m probably working on ideas that I came up with in Australia, or even on the previous trip to Australia, and vice versa. Everything gets mixed together.

Images float around on my computer for years, get recycled, accumulate. They’re just ingredients. They become disassociated from their origins. With the Dutch still-life material, people ask, “What painting is that from?” I have absolutely no idea.

Could you tell us about what you’re working on and what feels most generative in the studio at the moment?

I’m still working with colour separation, but the very large figurative Dutch master imagery has become less central. There’s a body of work that began with digital prints. I used dice to determine which drawing was used for which colour, orientation, positive or negative. With those works, it’s about randomness – letting go of control.

It takes me back to printmaking, back to the press, back to ink. You try to make one image and end up with twenty variations. The variations become the interesting thing.

I’m also working on very simple little landscapes. Change the amount of yellow, change the sky – you could make a thousand and they’d all be different. The base forms feel universal. Like Sugimoto’s horizons – images we feel we’ve always known.

I enjoy that fulcrum between abstraction and representation – between chance and recognition. I don’t quite know how it works, but it does.