Melbourne Art Fair 2026 | Troy Emery

- Troy Emery

- 19—22 Feb 2026

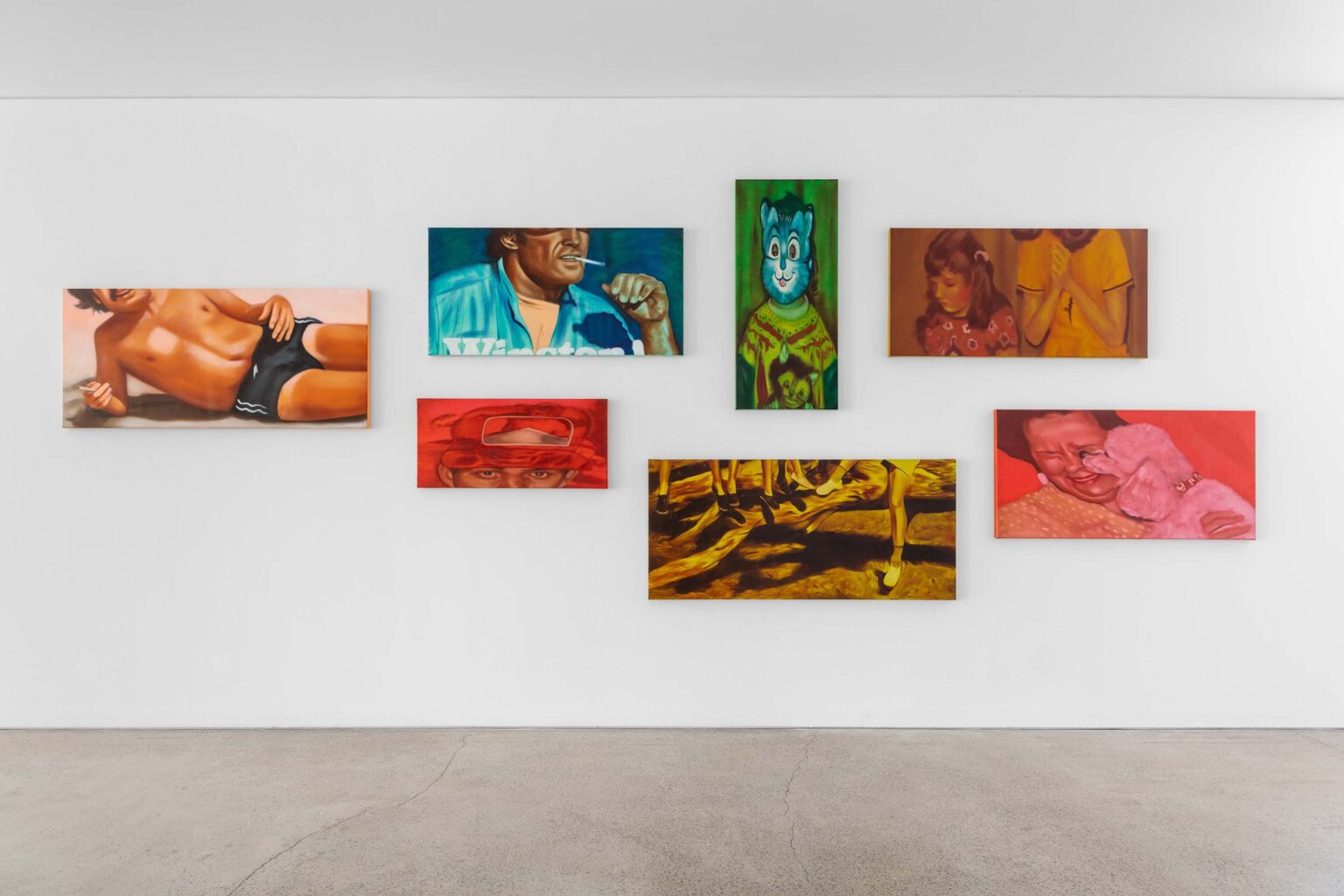

Troy Emery is among the most distinctive and accomplished voices in Australian contemporary art. The Naarm/Melbourne-based artist’s forthcoming showing at Melbourne Art Fair 2026 will be his first significant presentation in his home city since joining the Michael Reid Sydney + Berlin stable of represented artists in 2023.

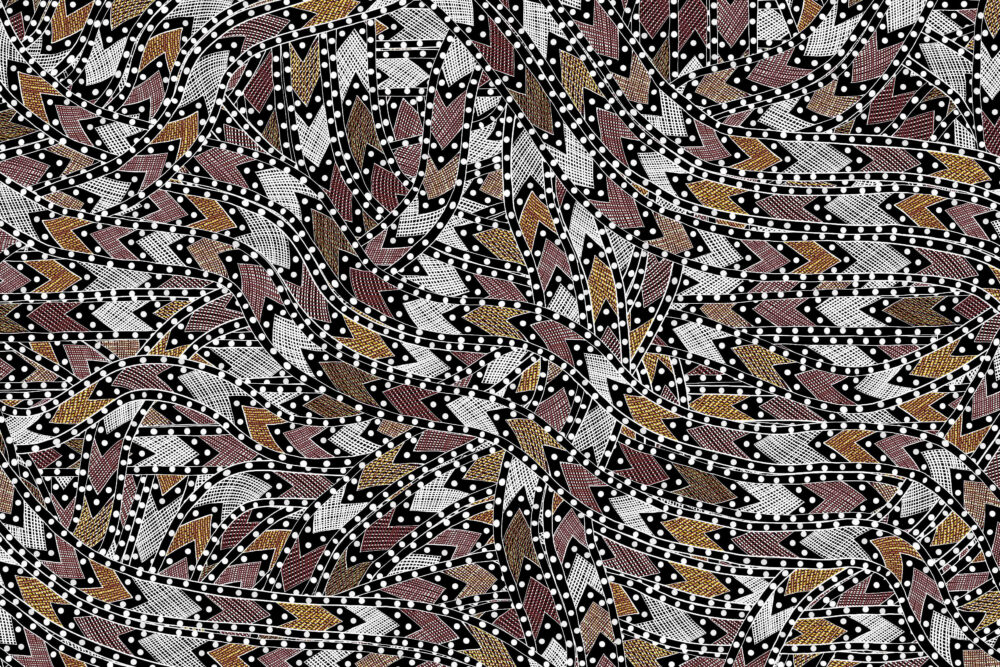

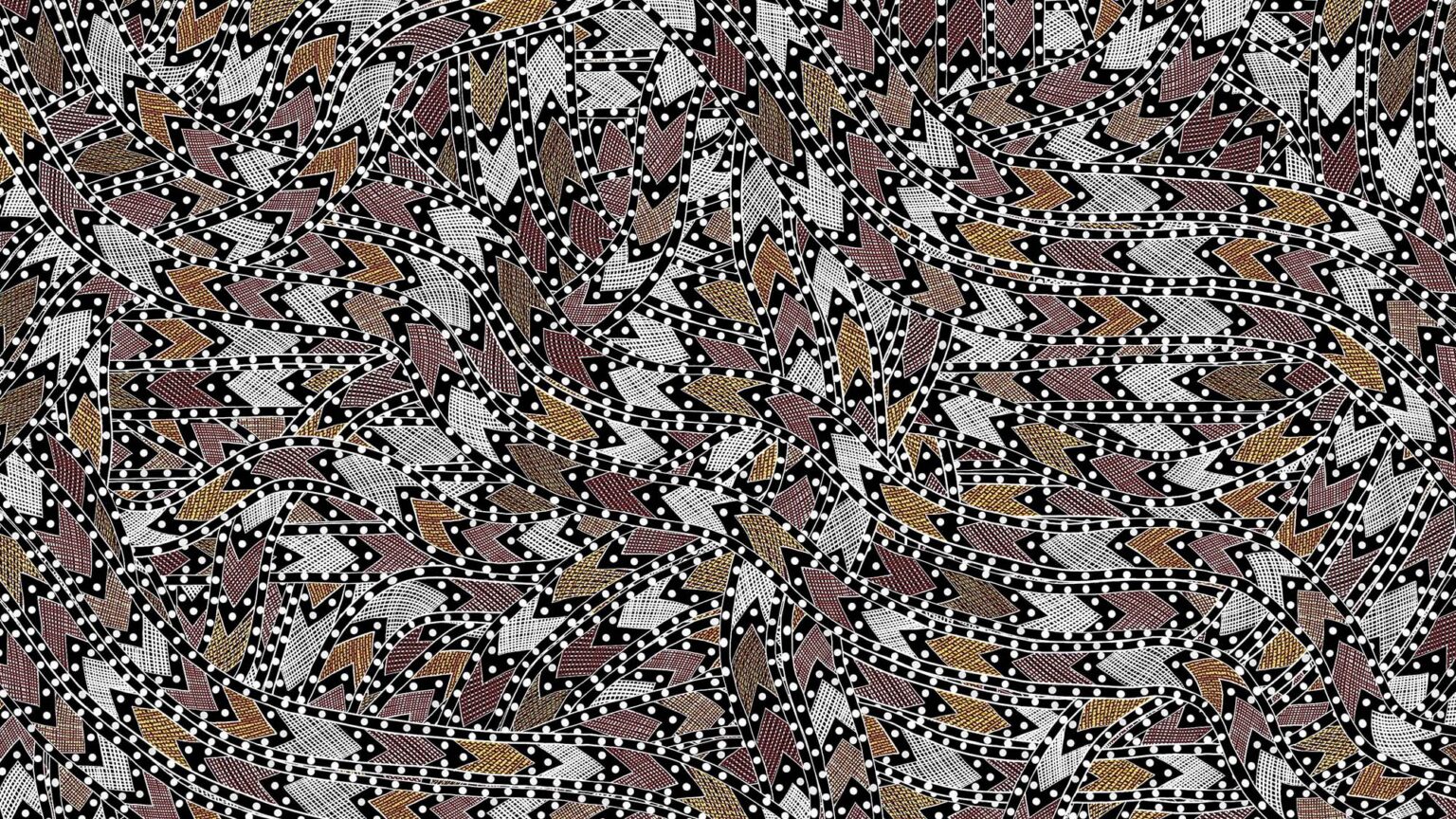

Remixing references to art and natural history, decorative crafts and the conventions of museum display, Emery’s widely celebrated soft-sculptural practice reflects on our position within – and apart from – the natural world, casting magnificent, otherworldly animal forms as playful representations of the unknowable other. Adorned with silky tendrils, soft knitted loops and dazzling Day-Glo threads, his tufty creatures exude a captivating mystique with a touch of camp – haughty and inscrutable beneath their lurid pelts.

Appearing to melt into their own being, Emery’s impossible creatures are meticulously fashioned by hand with a couturier’s precision and imaginative flourish. More recently, Emery has introduced hand-threaded, scintillating glass beadwork to his sculptures, further enriching a material palette that has, throughout his career, stood in opposition to the hard, masculinist conventions and monumental pretensions of art-historical sculpture.

At Melbourne Art Fair, a pride of his fringed and fabulous felines will slink, sashay and strike languorous poses on plinths and podiums throughout the Michael Reid Sydney + Berlin booth, appearing at once as decorative objects unto themselves and as emblems of ecological ruin and contemporary alienation. This presentation follows the unveiling of his largest sculptural commission to date, Guardian Lion – a sprawling, kaleidoscopic, illuminated landmark now soaring above Southbank and welcoming visitors to the arts precinct abutting the National Gallery of Victoria.

Emery has exhibited across Australia and internationally since completing a Master of Fine Arts at the University of Sydney in 2009. His work is held in numerous significant private and public collections, including the National Gallery of Victoria – where his room-sized pom-pommed panther was a centrepiece of Melbourne Now (2023) – as well as Artbank, City of Townsville, Goulburn Regional Art Gallery, Deakin University Art Museum, Deloitte Australia, Macquarie University Art Gallery and Maitland Regional Art Gallery.

For previews and priority access to works from Troy Emery’s forthcoming Melbourne Art Fair series, please email dean@michaelreid.com.au